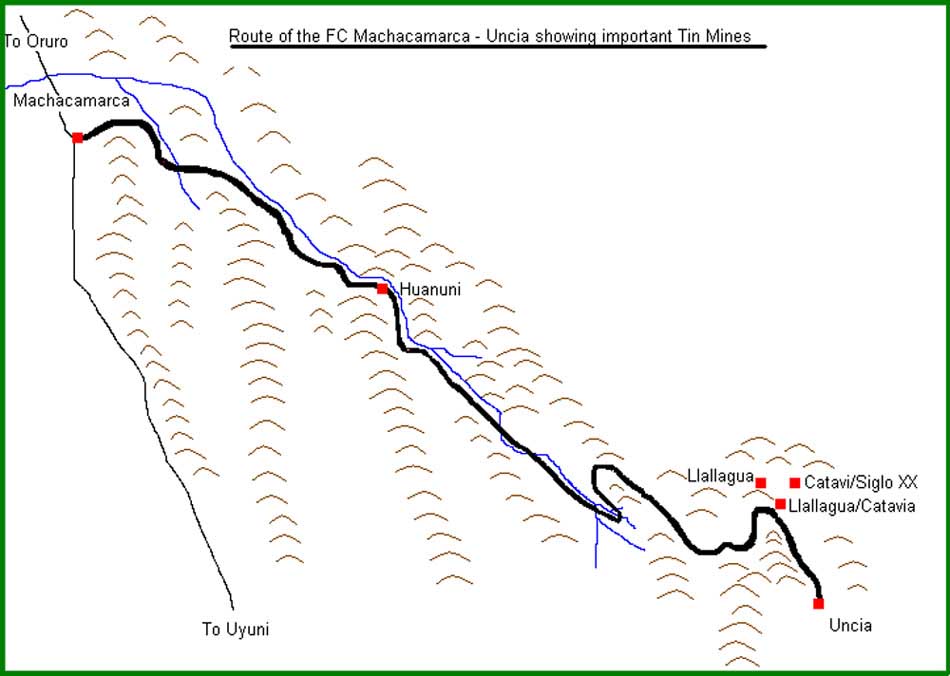

About 1939 the Patino organisation placed an order with Sulzer Brothers for a diesel electric locomotive suitable for hauling passenger or freight trains. The order was in many ways unusual. Not least was the terrain the locomotive was to work in, high up on the Bolivian 'Altiplano'. The Patino organisation operated the railway between Machacamarca & Uncia, which served the silver & tin mining centre around Uncia, Huanuni & Catavi. This 63 mile long metre gauge line which included the three mile Catavi branch varied in altitude from 12,200 feet to 14,400 feet, included a maximum grade of 1 in 40, although the ruling grade was slightly easier at 1 in 58 to 1 in 63.

The line had begun dieselisation early, in 1933 (?) two diesel electric railcars were obtained from Linke-Hofmann-Busch, Germany, powered by a six cylinder Linke-Hofmann Busch diesel engine. These railcars would operate with non-powered passenger coaches to provide more passenger capacity. At least Motor No.2 (with LHB builders plate dated 1931) survived to find a place in the railway museum at Machacamarca.

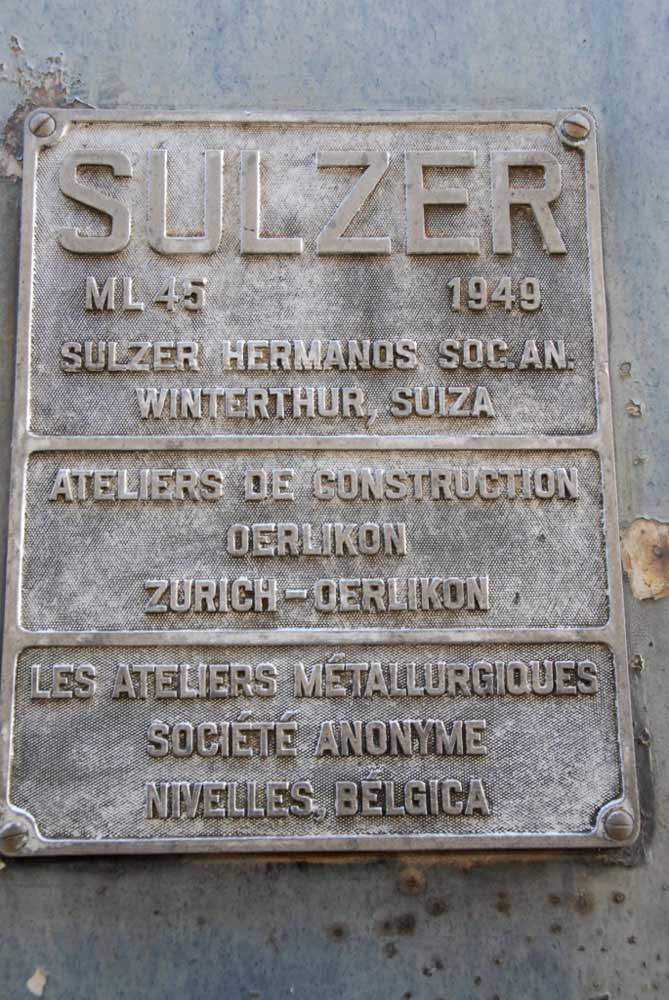

The placing of the order with Sulzer was Patino's introduction to diesel locomotives. Sulzer initially sub-contracted the mechanical portion to Henschel & Son AG, Kassel, Germany but the Second World War prevented Henschel from completing the order, and Sulzer were unable to find another builder to take up the project. With the war over the order was given to Les Ateliers Metallurgiques SA, Nivelles, Belgium. After completion in 1949 and before being exported, the locomotive was tested over the Rhaetian Railways. The profile of this line bore some resemblance to its future home line in Bolivia.

The operating characteristics of the metre gauge Bolivian line were severe. Temperatures ranged from -15C to +30C, radii on the line were as sharp as 230 feet (70 metres), maximum axle loading was 12 tons, top speed was a sprightly 37mph (60kmph). Passenger trains averaged 100 tons behind the drawbar, three hours was a typical journey time. Freight trains weighed upto 250 tons, four hours were required for their passage over the line.

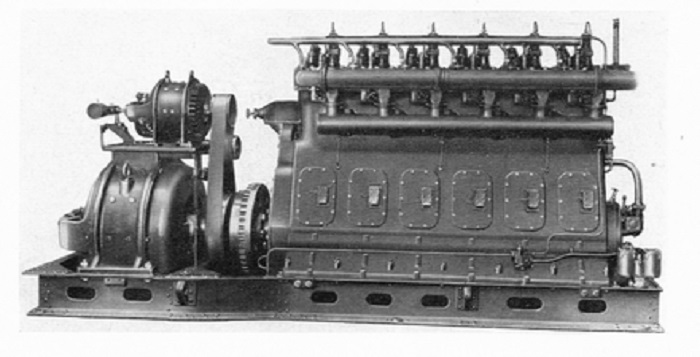

Sulzer provided for these conditions with a locomotive 50'6" in length and 9'1" wide, with two cabs and full width body riding on two three axle bogies. Power came from a Sulzer 6LDA28 engine. The engine was normally rated at 815bhp at 700rpm continuously (915bhp at 750rpm for the one hour rating). However due to the exceptional conditions on the Bolivian line the continuous rating was 650bhp at 700rpm (730bhp at 750rpm for the one hour rating). The engine was pressure charged on the exhaust gas system using a Sulzer turbo blower set using plain bearings for the shaft. Dry weight of the engine & blower group including the welded steel underbed was 8,450kg.

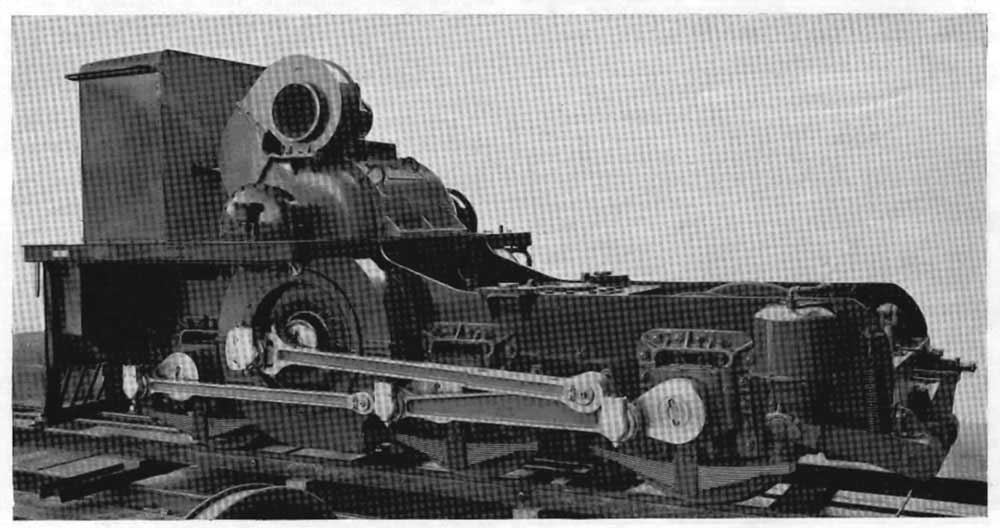

The electrical system, provided by Oerlikon to Sulzer specifications powered a pair of traction motors, situated in the two nose sections of the locomotive shell. Although bogie mounted the drive to the wheels was via a jackshaft. This was driven by a gearing through a special laminated spring wheel drive from each end of the motor shaft. The use of the drive via a jackshaft and coupling rods was most suitable for conditions involving low maximum speed and a demand for high tractive effort. Maximum tractive effort at the wheel rims was 33,000lb (15,000kg), continuous rated tractive effort was 16,750lb at 10.25mph, one hour tractive effort 21,600lb at 7.15mph. The wheels on the centre axle were flangeless.

Normal practices were followed in the construction of the mechanical portion. Each bogie frame structure was a completely welded unit. A series of light rods and an hydraulic shock absorber joined the inner end of the bogie to the underframe in an attempt to eliminate unwanted parasitic movement by the bogies. The nose above the bogies, as well as containing the traction motor was also home to the traction motor blower and the Nife batteries. Braking was initiated through a combined straight and automatic compressed-air brake system. The application of the brakes was graduated depending on the selection made. Maximum force from the locomotive's straight airbrake was equal to 60% of the weight, 80% of the weight was available from a full application of the automatic brake to locomotive & train. A single brake cylinder was fitted to each bogie, an Oerlikon reciprocating electrically driven compressor provided air for the brake & sanding gear.

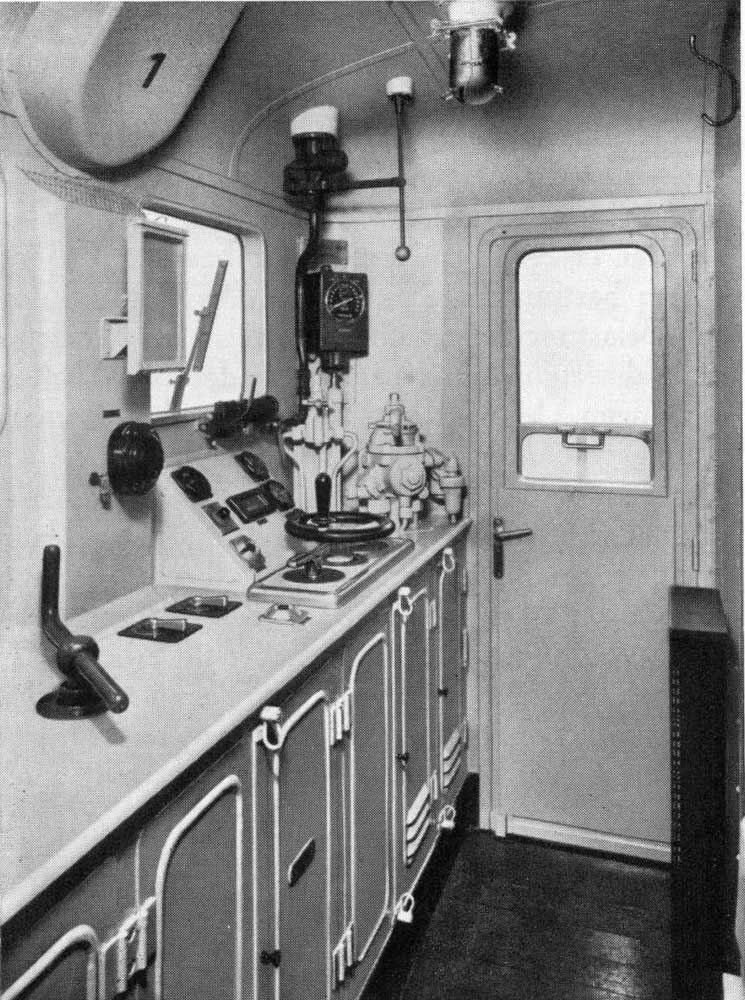

Empty weight for the locomotive was 66.4 tons, loaded was 70.4 tons, fuel tank capacity was 530 gallons. Electrical control gear was of the standard Sulzer type, eleven notches were available to the driver, one idling, two starting and eight speed-torque notches. This allowed the engine to run between 400 to 750rpm.

The above information/photograph/drawing is courtesy of an article in 'Diesel Railway Traction' from April 1950.

Ordered as No.20 but delivered 1952 as No.22 but carries a small plate on frame No.20, (later LDE846)

Ordered as No.23 but delivered 1956 as No.24 but carries a small plate on frame No.22, (later LDE847).

When the assets of ENFE were acquired by FCA the transfer did not include these two machines. At least one had been working at Oruro into the 1990's (possibly as late as 1993). LDE847 remained stored in the Patino's mine workshops at Machacaarca with much other equipment. LDE846 disappeared into the ENFE/FCA railway workshops at Oruro, apparently well hidden from visitors that from time to time toured the facilities.

![]()

April 2008 Update

The following notes and pictures have been graciously provided by John Middleton following his visit to Bolivia during April 2008.

Webmaster's note : it is perhaps ironic that in carefully studying the view of LDE 846 below, an educated guess as to its location can be made with the help of the shed on the left and the councrete boundary wall behind the locomotive. The wall marks the location of Av. Sgto Flores which forms the south-western boundary of the Workshops. Which means for your webmaster that the route taken by my La Paz - Oruro bus passed this very point, the bus was high enough to see over the wall, but mostly the coaching stock and steam locomotives were observed. Later on a walk taken around the exterior of the Workshops would have taken me within feet of one of the objects of my unusual trip to Bolivia!

![]()

April 2010 Update

In March 2009 the former mining workshops at Machacamarca opened as a museum containing many elements of Bolivia's railway history. Placed on exhibit is restored LDE847.

The view has been graciously provided by Nils Oberg through his posting of the image on Wikimedia Commons.

Information can also be found in 'Krokodile' by H-B Schonborn (GeraMond 1999, ISBN 3-932785-54-1)

![]()

The Machacamarca - Uncia route

The 60 mile long metre gauge railway line from Machacamarca to Uncia was opened in 1920 to provide freight service to the silver and tin mines located near Catavi, Huanuni & Uncia. The company also acquired a number of passenger coaches to provide a passenger service. Additionally to reach Catavi a three mile branch left the 'main line' just north of Uncia. Loadings were not great, 100 tons for passenger trains, 250 tons for freights whilst mixed workings did occur. Journey times were clearly affected by the many curves and grades found on the route, passenger trains typically required three hours, freight trains required four hours.

The mining property eventually passed to Comibol, whilst ENFE acquired the railway operation in 1987. After the line closed most of the infrastructure was removed, but the route of the railway line remains clearly visible along most of its length.

An aerial view of the area traversed by this railway line is similar in many ways to a sandy beach close to the waters edge where the wave action has created long uneven ripples in the sand parallel to the water. Walking along the beach in the direction of the ripples is relatively easy, but walking across these uneven sand surfaces would be more of a challenge. And so it was with the construction of this railway which had to deal with many ridges.

The western end of the line at Machacamarca was on the relatively flat altiplano with nearby Lake Uru Uru and Lake Poopo and thousands of square miles of salt flats to the south & west. To reach Uncia, about thirty three miles as the crow flies but some sixty 'railway' miles to the south east meant venturing into part of the vast Cordillera Central, a landscape of alternating ridges and valleys, generally trending from the northwest to the south. The route of the line would mostly encounter the ridges/valleys running in a south easterly direction, a major challenge for the engineers for they had five of these cordillera (Spanish: little strings), generally known as the Cord de Azanaques to cross in order to reach Uncia.

Although the railway is now long gone the route is paralleled by Highway 6 which runs from Oruro to Sucre, providing an insight into the conditions experienced by the railway builders. The railway took a more westerly & southerly route than the present highway and is considerably longer because of its twisting nature, required to keep the grades reasonable.

The first part of the route, the fifteen miles from Machacamarca to Huanuni was perhaps the easiest to engineer and operate. At Machacamarcha the Patino workshops were east of the Oruro - Uyuni railway line. A spur ran from the mainline to the workshops then exited the east end of the workshops and headed east directly towards the first ridge which rises to a height of 4,200 meters. As the line turned north a siding ran off to the south for a short way ending in a yard. The railway engineers were fortuitous in the location of Machacamarca, it lay just south of a large wash which had cut through several of the ridges, allowing both road and rail to avoid having to deal with a couple of the most westerly ridges. After a short distance the railway, and nearby Highway 1 followed a big shallow curve to work around the north end of the first ridge. North of the highway was a large mine facility, which appears to have been served by a separate siding from Machacamarca. The railway then headed in a south easterly direction following the eastside of the ridge. A small facility was passed at a point where the line turned east for a short distance before turning back towards southeast. After a considerable length of relatively straight track a river came in from the east side and followed the railway until the river was crossed and the railway turned east, made possible by a ridge ending here allowing unimpeded access to the next valley, the current elevation was about 3,800 meters. In many places the trackbed is now used for local access, with a number of bridges in place to cross the washes.

Once into the new valley the railway continued its south easterly direction, now joined by a river and a stub of Highway 6 on the east bank. Generally the line tried to avoid running too close to the river, but eventually crossed one branch of the river on a 150 foot span. The line took an easterly direction following the main channel of the river. Shortly after crossing the river the railway formation has been washed away for about 1,500 metres. On the north side of the river were some large mining facilities, as the valley closed in the railway entered the mining town of Huanuni paralleling the river. The railway ran through the town, north of the river at the east end of town was a large mining facility which at some point rail access.

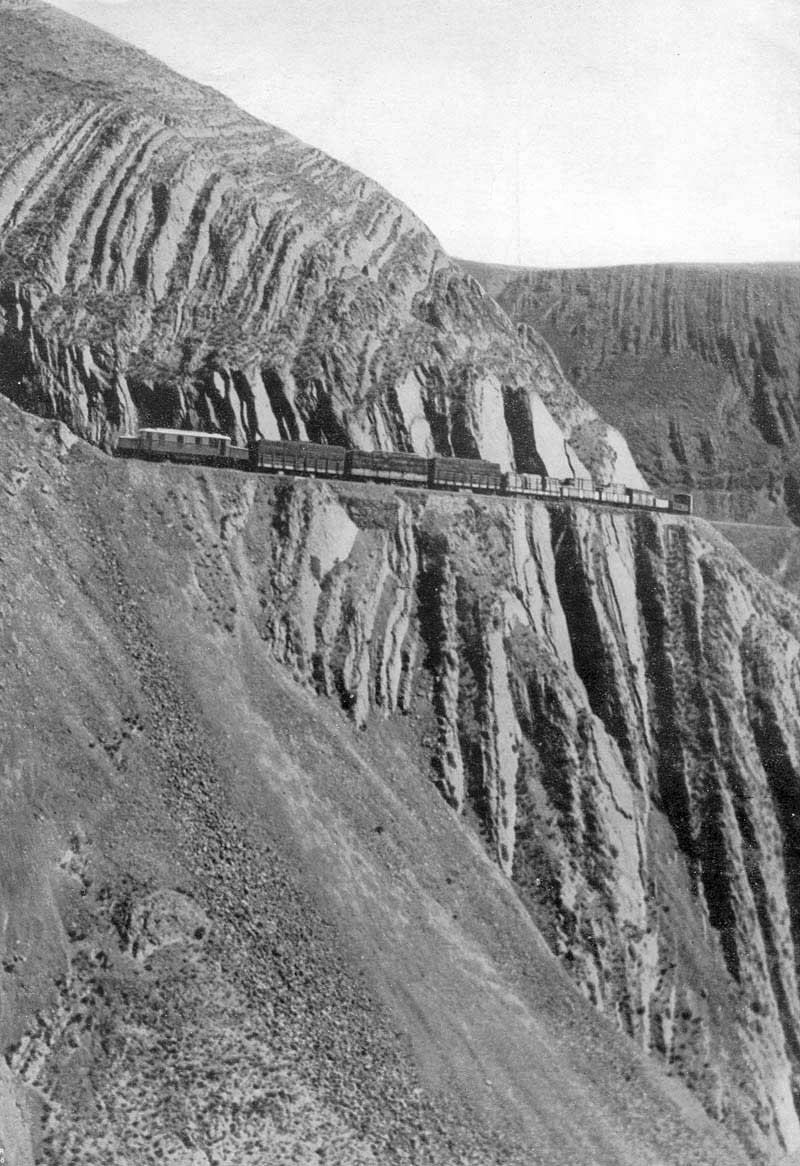

The next section of line ran from Huanuni to the summit of the last ridge, with the route required to gain altitude in its later stages. After leaving Huanuni the railway now entered a narrow steeply sided canyon, at an altitude of 3,950 metres. The canyon turned to the south east and must have been quite spectacular when viewed from the train. The geography here becomes a little confused, fortunately the river still provided a route to head southeast and soon crossed the 4,000 metre mark and heads south. A number of tributaries join from the north side, but the railway remains with the south fork of the river until it becomes smaller and hemmed in by a steep sided valley, with dramatic outcrops on the north/east side. For most of its length to this point the track formation has been widened for use by road vehicles. Just before the route crosses the river a large landslide has partly covered the trackbed. A large bridge carried the railway to the east bank, now running on a ledge carved out of the steep side of the mountain. Shortly the river and line turned east followed by a big loop to the south where the river is crossed again. A road now comes alongside the river & railway, the road soon joins the route of the trackbed, again this has been widened and graded for vehicular traffic. It appears the route is now used to move agricultural produce out of the area, particularly large bales of hay. A number of small streams were crossed that came in from the south.

The railway continues to make turns to the east and south and the formation is again washed out in places by the river, elsewhere the multitude of dirt tracks has also obliterated the formation. After about eleven miles of this relatively easy going following the river since Huanuni the railway crosses to the east bank, although the bridge is now gone. The valley has now reached an elevation of 4,250 meters, a small basin is crossed with tributaries coming in from several directions, but still the very well defined ridge to the east prevents easy access in the direction of Uncia. A short distance south of a fork in the rivers the railway crossed the south tributary with a bridge and long embankment. The route can no longer take advantage of the water courses, from here the line heads north, curving round a hill to reach the northern tributary, which is crossed by means of a sharp curve and a small bridge. From the valley floor to the top of the last ridge its about three miles as the crow flies, but the route taken is probably double that. The line now climbs up the side of the mountain which it had just followed for several miles, gaining altitude using many curves and embankments, including several dramatic 180 degree curves. Altitude gained since leaving the south fork of the river was about 125 meters. This section must have been a dramatic route to ride upon.

Having climbed up the valley side the line makes a big loop to the south reaching 4,400 metres, it skirts a shallow valley and parallels a well worn dirt road before turning north east on a large curved embankment. Fifteen hundred feet after the curve is a triangle of lines, possibly used for the turning of steam locomotives since the summit of the line has been reached. Just to the north of the triangle is Highway 6. In turning southeast the last north/south ridge is now crossed, ahead lies the descent towards Llallagua and Uncia, which for the first mile or so descends on the east side of the ridge, at this point the elevation is now about 4,400 metres, with the highest parts topping out at about 4,500 metres. Here it crosses the imaginairy line between the Oruro & Potosi districts. After a short distance of easy going the route returns to one of many sharp curves, embankments and cuttings. The route is still trending south-east but is severely challenged by the continued crossing of valleys & ridges. The general drainage is to the east, there are several deeply incised valleys, but the railway ignores these and takes a twisting circuitous route to make its way generally south-east.

As the crow flies its about eleven miles from the summit to Uncia, for the railway its probably double that! The first four miles are relatively straightforward but with increasing curves, cuttings and embankments as the route progresses south-east. The route scrambles around washes and ridges, almost uncertain as to which is the best route to take! Some of steeply sided hills rise to about 4,700 metres.

The line finally reaches a point where it can cross the head of a large wash, then heads north-east with a further sequence of curves, embankments and cuttings. It circumnavigates another deeply rutted wash, in some instances erosion has washed away the formation. After trending north the line swings sharply east and loops back on its self, now on the east side of a north/south ridge. Since leaving Huanuni there have been no villages to speak of, now the line is perched on a mountainside overlooking Llallagua & Cativa. The line makes a sharp turn to the east, and becomes a dirt track for a short while. It skirts the south-west side of Llallagua, before heading east, passing through the only tunnel on the route, which is about 400 feet in length. A short length of meandering level track is followed by the return of more curves, embankments and cuttings.

The route is now due north of Uncia, but its route will not be a straight line. It is now paralleling Highway 6, but the highway follows a much straighter route. Possibly one of the larger cuttings on the route is encountered as it begins its journey south. More severe curves and embankments follow, in between sections of easier going. The line is joined now by the remains of the branch from Cativa. Now keeping to the higher ground the route avoids some of the eastward trending washes, in doing so the line reaches the proximity of Uncia perched high up on a ridge. To reach the valley floor on which the town sits the line heads south-west and drops slowly down the steeply sloping and rutted valley side. The line enters Uncia, elevation 3,850 meters, at the west end of town, the route taken by the line is now unclear due to development over the years, although some of the streets suggest they were built on the abandoned route.

![]()

Despite successful orders during the 1960/70's for a series of Bo-Bo-Bo locomotives from Japan, ENFE ordered two diesels from SLM/Sulzer which were delivered in 1985 - as can be seen from the builder's plate from 981.

Although these two locomotives were built by SLM/Sulzer they were powered by an MTU 12V 396TC 13 diesel engine producing 1,180kW at 1800 rev/min, for use in Bolivia the rating was set at 900kW (695kW continuous at rail). Electrical equipment was provided by Brown Boveri, Vienna. Maximum speed was 65 km/h. Weight 60 tons.

LDE 980 SLM/Sulzer #5294 of 1985

LDE 981 SLM/Sulzer #5295 of 1985

All the views above of 981 are received with thanks from Colin Churcher, taken on a visit to Viacha workshops during May 2003. The locomotive has been out of service for a while, although sister 980 was active at Oruro. (I had seen 980 at Oruro during my trip to Bolivia during October 2002, but only at a great distance, and I was not familiar with what I was looking at!!)

If you are interested in South American railways Colin has a website describing his adventures in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia & Chile. Go to my links page to find Colin's link.

![]()

The notes below provide some historical detail about Simón Patiño and the Patiño empire he created, which included the building and operation of the Machacamarca - Uncia railway.

The line that operated the two 'Sulzers', from Machacamarca to Uncia was a relatively late arrival on the railway scene in Bolivia. The line was privately owned and its connection with the mainline at Machacamarca would allow a more expeditious means of exporting the tin dug out of the ground at Uncia, Huanuni & Catavi. Prior to the arrival of the line at Uncia, the refined ore was shipped by llama and cart to the nearest railhead. at Machacamarca.

Construction was completed in two phases, the first 37 miles opened in 1920, the remaining 23 miles to Uncia opened a year later. A three mile branch was also constructed to Catavi. The line was built as metre gauge.

The Early Years

The construction of the line and the mine facilities that it serviced were made possible by the good fortune of Simón Iturri Patiño (born Cochabamba, Bolivia June 1st 1862, died Buenos Aires, Argentina April 20th 1947), who built a vast fortune out of the minerals, principally tin & silver that could be found in the rocks around Uncia. At the time of his death he was one of the world's wealthiest men. Patiño is believed to have spent his early years growing up in the Oruro area. In the 1880's he had worked in the famous Huanchaca silver mine (Compania Hunanchaca de Bolivia). He transitioned to the supply firm of Fricke in Oruro to handle the store's collections. In 1894 a deed of land was accepted by Patiño for the modest debt of a prospector. This did not sit well with the company, they considered the land to be worthless and fired Patiño and possibly required him to make good on the debt.

The deed was for rocky land on the side of a mountain located at Llallagua. For three years the site was worked over with little result, but in 1900 the claim eventually proved to be far richer in minerals than anyone had imagined when a very rich vein of tin was found. The strike was called 'La Salvadora' (The Savior). With the resources generated from this mine Patiño built up control of nearby mines and other significant mines in Bolivia, including Catavi, Huanuni, Siglo XX (20th century) & Uncia. As the 20th century opened this exploitation of tin would make Bolivia one of the world's major tin suppliers. It would also contribute to a period of stability in the country and allow development of other industries.

The Siglo XX mine was for most of the century 'the richest tin structure and most productive in the world'. The area had over the centuries seen much mining for silver, but it was only the transition from silver to tin mining in the late 19th century that saw the dramatic growth in operations. When silver was the principal ore mined any tin retrieved had been used locally for lining water tanks or in the brewing processes. After mining commenced in 1903 it produced about 30% of all Bolivia's tin and 6% of the world's tin, a total in excess of one-half million tons of tin (as at 1974). This output and that of the other mines owned by Patiño created the economic base for Latin America's first and only multinational corporation - with eventual interests in North & South America, Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Prior to the arrival of the miners the mountain of Llallagua supported little more than patches of potatoes, a staple crop of people living in the Andes. Llallagua is the Quechua spirit that provides abundant potato harvests. As mining opened up the veins some were discovered to be over three feet wide with the ore containing 65% tin, so rich it was exported without passing through the concentrating mill.

Patiño was a shrewd businessman and looked to expand his empire vertically. He was aided by the dramatically increasing market price of tin - it quadrupled between 1896 and 1917, whilst his production costs remained relatively stable, leaving the company with an extraordinairy profit margin. This was also aided by the decline in European tin production, the mines in Germany were played out and those in Cornwall, England had greatly reduced output, and at a time when the tin canning process was expanding greatly. Once brought to the surface the processing of the ore followed long established but archaic practices which relied heavily on local labour and methods that would not be able to handle the increasing volumes.

Patiño sought to industrialize the operation. In 1901 plans were laid down for the $1 million Miraflores concentrating mill, which would contain Bolivia's first diesel engines. The mill came online in 1904 and allowed output of processed ore to quadruple during its first year of operation. In 1918 Sulzer Brothers provided a 600hp diesel/generator set for use at Uncia. The equipment was shipped by sea to Antofagasta, Chile. Here the motor was broken down into five sections and delivered by rail to Machacamarca. From here thirty miles of the branch to Uncia had been completed. Where the railway ended the machinery was loaded onto carts hauled by mules, one large component, almost nine meters long and weighing eight tons required a specially built cart. The Uncía mill required a lot of power, cable cars brought the ore to the facility, six crushing & pulverising mills reduced the ore followed by a visit to the cylindrical mills. A magnetic separation process was applied to the low grade ore.

The railway line to Uncia would not be completed until 1921, at which point the movement of ore by llama and cart was discontinued. The capacity of the original Miraflores mill would be greatly exceeded by the opening of the Victoria concentrating mill at Catavi on the other side of the mountain. In addition to the imported diesel/generator sets the demands for electric power were met by the creation of two artificial lakes, producing hydroelectric generating capacity at a high point of 16 million kW.

Original motive power for the line was a number of powerful tank locomotives built by Orenstein & Koppel, Germany, some were semi-articulated Mallets.

Consolidation & Overseas Expansion

In 1908 Patiño made his first trip to Europe, to learn the challenges of the tin market and to acquire half-ownership of the German smelting firm of Zinnwerke-Wilhelmsburg, which was refining nearly all his ore. The United States National Lead Company was the other half-owner of this company, they also managed the smelter. This was the first of many moves by Patiño in the tin market to gain power in his drive to dominate the Bolivian and international tin industry. This link with Europe was solidified in 1912 when he set up residence in Hamburg. World War One required changes to be made, Patino moved to England, directing his ore to the Williams, Harvey smelter at Liverpool. The leverage of National Lead & Patiño was used in 1916 against the English company to break their monopoly on ore smelting. Eventually National Lead acquired one-half interest in the English company, then selling on one-third of its share to Patiño. By 1929 Williams, Harvey was entirely owned by Patiño interests, On the opposite side of the world the major Malayan tin-mining companies attracted Patiño's interest, buying large quantities of their stock.

From 1910 Patiño began to consolidate his Bolivian mining empire, hoping to achieve economies of scale. This included the purchase of active and inactive mines in the area. During the 1920s Patiño was said to have a greater annual income than the Bolivian government. Unfortunately at the same time a heart condition made his return to Bolivia not recommended. After 1924 (when he owned fifty percent of the national production) he lived in Paris, New York and finally Buenos Aires. His wealth and European residence allowed hin to run in diplomatic circles whilst in Bolivia, through his wealth, he wielded much political power.

Although Simon Patiño could not return to Bolivia because of health concerns he remained a patriot of Bolivia providing the town of Cochabamba with electricity and the establishment of a new bank in Bolivia. He also set about dealing with a rival Chilean mining concern that owned the Compañia Estañifera de Llallagua, a competing mine at Llallagua. From 1914 under the secret direction of Patino two British firms were used to buy stock in the Chilean company held at the Santiago stock exchange. National Lead were also involved in this subterfuge, by April 1924 Patiño announced ownership of the Chilean company, with his interests holding two thirds of the stock. The two competing mines at Llallagua were now combined under Patiño's ownership.

Now with a very firm footing in the Bolivia tin extraction and smelting industry, Patiño continued investing in Far Eastern & African tin production & smelting. He successfully diversified into other unrelated investments in North America & Europe creating the basis for a well integrated and growing fortune.

Surplus Production and the Great Depression

But time was marching on for Bolivian tin mining. The extraction of tin from alluvial deposits in South East Asia provided stiff competition for the Bolivian ores, in particular the high quality of these ores and the cheaper labour costs. The price of tin fell 75% between 1926 & 1932, Bolivian production fell by two thirds during the same period. Over production following record high prices in 1926, declining demand and the arrival of the Great Depression and the Stock Market crash all took a heavy toll on Bolivian tin mining. At the height of production in 1928 the Siglo XX mine had approximately 87 miles of tunnels accessible by rail mounted ore-cars and 43 lodes with 295 branches under exploitation. Further growth of this and the other Bolivian mines would be seriously impeded by the previously mentioned factors and the exhaustion of the higher grade ores. Since the Patiño companies generated possibly a sixth of Bolivia's revenue and employed as many as 30,000 people any potential scaleback of production would have a major impact, this was at a time of growing unrest in the workforce as communist agitators sought to infiltrate the work force. Riots in September 1930 required the use of troops to re-establish order. However major cuts in employment and mining activities did take place, frequently mining methods reverted to those from earlier times to save costs.

To save the Bolivian tin mining industry Patiño looked for greater access to the Malaysian mines and set about implementing global production controls for tin. No doubt the Malaysian companies were well aware of Simon Patiño's earlier methods of acquisition and sought to limit foreign control of their companies. During 1933 production limits were implemented, the 1933 production would be one third of the 1929 totals, by the end of 1933 tin prices had started to rebound. But Bolivia was now entering a period of war with Paraguay, many experienced miners had joined the army which led to a shortage of labour at the mines. To mitigate this many old workings were now reworked, ore that once was considered virtually worthless was now processed. Labour shortages continued despite the use of native Indians and Peruvians & Chileans. Turnover was high since the workers frequently only accepted ninety day contracts, strikes were also frequent, these were blamed on agitators. It is perhaps tragic to note that the extensive Patiño archives in Paris detailing fify years of the mine's operations contain in the words of historian Querejazu "there was not a single document analyzing the political and social situation, even though the growing agitation among the workers and repeated errors of government made the future of the mining industry and the nation's economy increasingly insecure."

The declining quality of the ore and the lack of new high quality lodes spelled certain closure for the mines, between 1938 and 1952 the average ore grade at Siglo XX declined from 2.45 to 1.11 per cent tin. However technological innovations which greatly reduced labour requirements averted closure, allowing annual tonnage to reach 10,500 tons between 1947 & 1952. But the labour situation remained a time of strikes, uprisings and the formation of unions, Siglo XX's miners formed the largest and most militant unit of the Federacion Sindical de Trabajadores Mineros de Bolivia (FSTMB), the national union founded in 1944.

Death and Revolution

In the midst of all these events Simon Patiño died in Buenos Aires on April 20th 1947. His remains were returned to Bolivia, being buried in Cochabamba, leaving his widow Albina Patiño to become president of the Patino Mines & Enterprises Consolidated (Inc.), Albina Patiño and her children controlled 80% of the stock of a company which at the time controlled 35% of the world's supply of tin.

With the labour movement having grown in strength and influence over the previous two decades and with the people seemingly ready for serious change, the Revolutionary National Movement (MNR) with Victor Estenssoro as its leader won a clear victory in elections held in 1951. However the army placed General Hugo Ballivan in the president's position. The expected confrontation came in early April 1952 when armed MNR members confronted the government forces in La Paz and other parts of Bolivia. It took three days and the loss of six hundred lives for the MNR to take its rightful position in the government of Bolivia.

On April 15th 1952 the victorious Estenssoro arrived in La Paz, having returned from exile in Buenos Aires. The energy of the 'revolution' moved quickly through the government, with reforms and changes being quickly instituted, one of which was a demand for the nationalisation of the mines.

The mines were nationalised by decree effective October 31st 1952. That day MNR President Estenssoro visited the Catavi mill and the mining camps of Siglo XX to announce the nationalization of the mines before a cheering assembly of miners, peasants and politicians. Although the occasion was one of many festivities which lasted for many days, it was not mentioned that the mine was in decline and output in the post-Revolution era would never match tonnage from earlier years.

The new organisation, the worker-run Bolivian Mining Corporation (COMIBOL) took over the operation of 163 mines and 29,000 workers previously controlled by the mining barons Aramayo, Hochschild & Patino. Originally demands had been made to pay the mine owners nothing following the seizure of the properties. However the three owners would receive $27 million for the loss of the mines. The Patiño family were able to force an early repayment plan upon the Bolivian government because of external political pressure and their control over the crucial Williams, Harvey smelter, the sole Bolivian tin concentrate smelter still operating in the world.

It was amidst all this change and upheaval that the first of the diesel powered locomotives for the FC Machacamarca - Uncia railway arrived from Europe during 1952.

Freight traffic totals:

1925:

53,000 tons tin barilla

16,000 tons of lead & silver slag

11,000 tons of silver

large quantity of other minerals.

Sources:

Bolivia: The Price of Tin, Part I: Patiño Mines and Enterprises; by Norman Gall.

Sulzer Motores Diesel, VIII 1929 (Spanish printing).

![]()

The two locomotives which worked the Machacamarca - Uncia held the record for the highest altitude operated by Sulzer powered diesel locomotives.

However two decades earlier the Sulzer sales representatives of the 1920 & 1930's had left their imprint on Bolivia with the sales of stationary power generating plants in a number of locations. Whilst this has absolutely nothing to do with the original purpose of this page, the need to explore a little further has resulted in the information below!

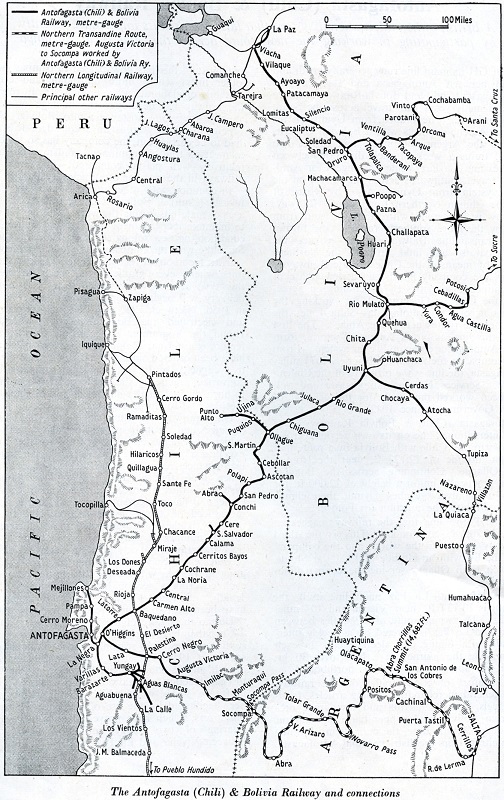

Guaqui - La Paz Railway Company.

This was the first electrified railway in South America opening December 1905 to provide service over 5.5 miles of heavily graded track between El Alto and La Paz. The elevation change between El Alto & La Paz is about 1,400 feet, this short line had a ruling grade of 1 in 18, with a maximum grade of 1 in 16, which dictated that electric traction be the motive power of choice.

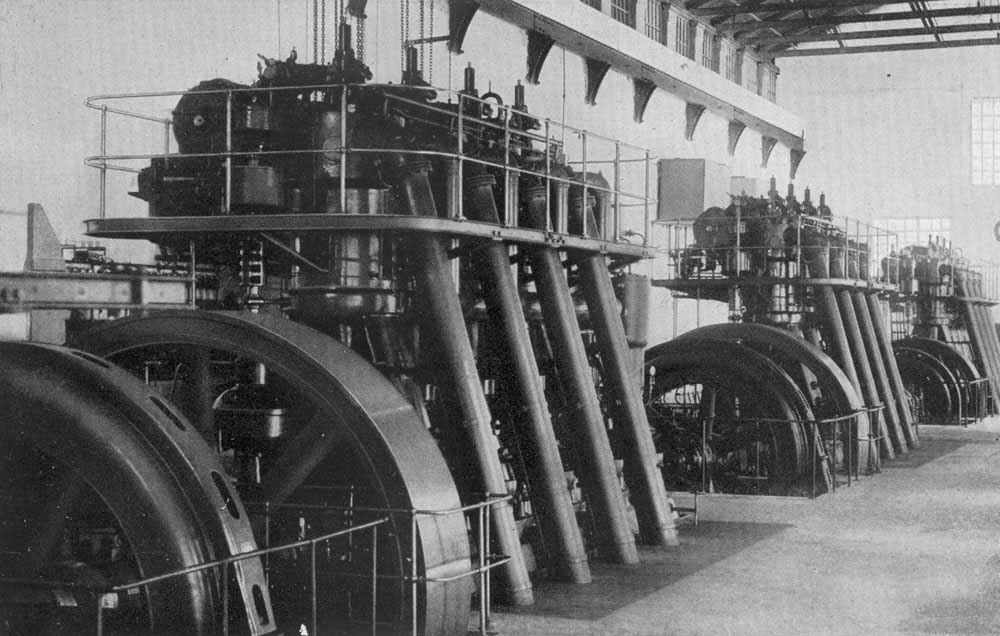

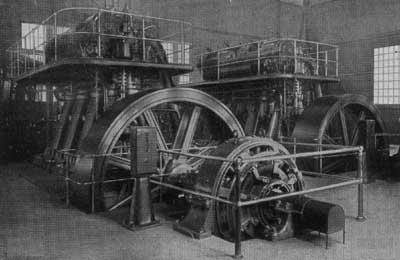

Initially a gas supply provided by a Mond plant drove 600hp engines for the electric supply to the line. In 1914 this plant was replaced by a new installation at Pura Pura (La Paz). Installed here were two 400hp Sulzer four cylinder four cycle diesel engines. A report dated about 1929 noted that the diesel engines had performed satisfactorily in regular daily service with the minimum of repairs required.

During the 1970's a large modern highway was built to connect El Alto to La Paz, this cut the electrified route in several places and effectively closed the route. A short section of track in La Paz remained electrified for freight car movements, but by this time electricity was being supplied from the public grid.

| In reporting on segments of the railways of Bolivia, the 1951 Railway Gazette Overseas edition included a view of the Guaqui - La Paz railway on the severe grade (1 in 14) between El Alto & La Paz. The electric locomotive shown is the English Electric 640hp No.32 (serial 768/30). Down in the valley to the left of the locomotive is the city of La Paz, whilst in the center background is the spectacular Mt Illimani. |

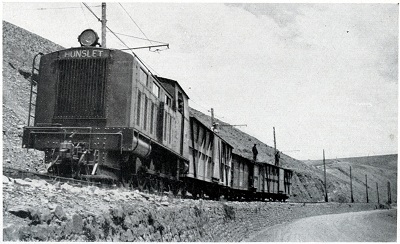

| Also operating over the steeply graded electrified line was a Hunslet diesel-mechanical, the engine being equipped with a pressure charger due to the 13,000' elevation. |  | The power generating plant located at Pura Pura was at an altitude of 12,500 feet. In this view are the two 400bhp four-cylinder, four-cycle diesel engines which provided electricity for the Guaqui - La Paz Railway. |

Milluni Tin Mine.

This tin mining complex was situated about 20 km north of La Paz at an altitude of 14,900 feet. Installed here was a four cycle airless injection two cycle diesel engine & at the time of its installation it was reported to be the highest diesel engine plant in the world. During the wet season the diesel engine was only required at times of peak load, but during the dry season the diesel engine provided all the electrical needs of the tin mine.

The ore content here was about 2%, initially mined in open pits, then in burrows. Later a British company used horizontal drifts into the mountain to work out the four foot thick veins. By this method output of ore was about seventy five tons per day.

Miners from Milluni assisted in the insurrection which overtook Bolivia in April 1952. The miners marched to La Paz, occupied the railway station and seized a train of munitions. The next day the military junta fell.

Slumping tin prices in 1985 saw the mine abruptly cease production. Now all the mine produces is a pollution of the local water supply, though a low-tech solution (bacterial sulphate reduction) using supplies of locally available llama dung provides a realistic and cheap answer to the pollution problem. And since Bolivia has virually no scrap recycling industry and this mine is in the middle of nowhere, one wonders if this Sulzer engine remains at the mine facility.

Carabuco Power Station.

This power station supplied electric power to a zinc & lead mine at Carabuco. The mine is situated on Lake Titicaca west of La Paz at an altitude of 14,000 feet. The diesel engine was transported across Lake Titicaca in a boat special adapted for travel over the shallower portions of the lake. The four cylinder engine developed 200hp at 333rpm. An out of adjustment valve gear caused the engine to suffer an explosion in a cylinder which bent the connecting rod and damaged the liner & piston. Until new parts were obtained the engine remained in service operating on three cylinders.

Portugalete Power Station.

This silver mine was situated in Portugalete (Department of Potosi), the village is at an altitude of 14,066 feet, but the actual mine is 1,000 feet higher. A diesel engine was installed here to provide a power source for the mine.

Portulagete is close to the town of San Vicente, the location where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ended their days. Which is somewhat ironic as the movie was part of the inspiration for me to make my trip to Bolivia. That a location near to the places where Butch & Sundance wandered would later utilise a Sulzer engine, another connection with my trip to Bolivia might perhaps be considered an interesting coincidence.

![]()

![]()

Sources:

Sulzer Technical Review #4 1929

Page added November 11th 2002

Last updated April 10th 2022.

Return to Sulzer page

Return to write up of visit to Bolivia, October 2002

Return to Picture menu