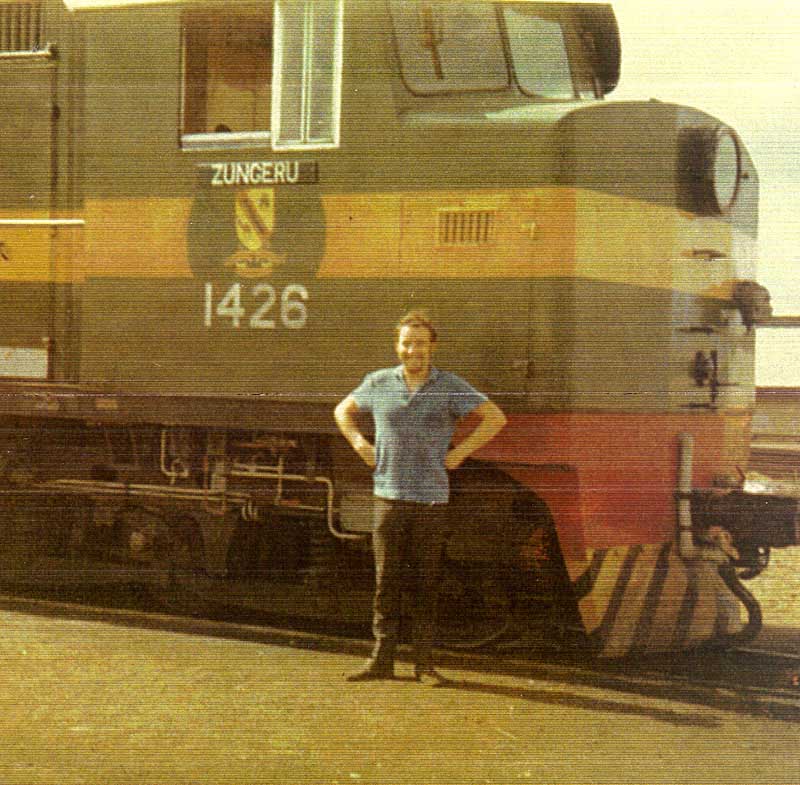

Our storyteller catches the Nigeria sunshine alongside 'Station' Class 1426 'Zungeru' at Zaria, Nigeria.

All photographs are from the author's collection unless otherwise stated.

The Beginning

My service career commenced with Sulzer (London) during 1965, initially assigned to Loughborough, followed by a short stint at Stratford Works. It was then off to Crewe Works for about eight months. By the end of 1966 it was back to Loughborough for work on the Class 46's and the final Class 47's. Three months in Nigeria followed. On return to the UK I was assigned to Gateshead until June 1968. Another trip was made to Nigeria, this time for twelve months. It was back to the UK with HS4000 being a major part of my responsibilities, now based in Derby and also covering the WR, LMR & ER on Sulzer related matters. Following the closure of the Traction Division I spent three years with the Marine Department before leaving Sulzer in 1979.

The notes below are not necessarily in chronological order and are the result of sifting through a long series of email exchanges between myself and Geoff. This is not intended to be a complete discourse on the happenings of Sulzer in the UK, rather the highlights of an occupation that was vital to the operation of the railways, and one which seems to have received little coverage in railway circles.

The British Railways Class 47

One of my early duties involved the commissioning of the engines for the Class 47's. These were sent from Vickers Armstrong, Barrow to BR, Crewe & Brush, Loughborough, it was my job to ensure that the engine was installed correctly. This would include load testing, setting alarms, governor, rectifying any snags, then a trial run down the Midland mainline. I was responsible for commissioning the engines placed in the last two Class 47's to enter service, D1960 & D1961, way back in 1967.

A former Brush Traction Dept test engineer identified the above view as the London Road curve, Derby. The locomotives have most likely completed their twenty five mile light engine test run from Loughborough and have perhaps already been onto the weighbridge and now await their loaded acceptance trial (1T38) Derby - Chinley (or Stockport) - Derby - Syston - Derby. The engineer records two highlights of the day on these test workings, passing the Mirlees engine factory at Stockport and giving the workers the thumbs down, followed by our passing through Loughborough station around 12.45 at speeds of 97-103mph, with horns blaring well before the station to alert the Brush employees that were lining the fence during their lunch break that another successful locomotive had been completed. On occasion the opportunity was taken to drive the locomotive, the BR Riding Inspector saying 'Its still your locomotive till we get back to Derby, you might as well drive it'. I never refused.

British Railways Class 48's & the 12LVA24

The Class 48's comprised five locomotives numbered D1702 - D1706 fitted with the Sulzer 12LVA24 power unit. They were delivered to Tinsley (41A) during the last quarter of 1965, apart from D1704 which was delivered during July 1966. All (apart from D1702) were transferred to Norwich between April & June 1969 where they were put to work on the Liverpool Street expresses. All returned to Tinsley in February 1970, prior to entering Crewe Works to have the 12LVA engine replaced by the more familiar 12LDA28C.

The Class 48's suffered with problems on bottom end bearings, although one of the Class 48's never experienced a failure of this type. Sulzer blamed BR for the failures. After the Class 48's were withdrawn we were discussing operating problems with people from SNCF. They too had suffered some of the same problems with the bottom ends. In their case Sulzer in Winterthur had implemented a minor modification to the bottom end assembly. This information had never been transmitted to Sulzer UK or BR.

The connecting rod bottom end bearing failures involved a locating pin in the cap half. It was present to ensure that the bearing halves were in the right position. It was later discovered that it fouled the bottom half shell. The failure was started by a high spot, caused by the locating pin, on the running surface of the bearing. This eventually affected the flash chrome plating of the crank pin and stripped it off. As a result the bearing usually seized and turned inside the rod bottom end. These failures mainly occurred whilst the locomotive was in service, either the driver would hear unusual banging noises and shut the engine down, or low oil pressure would occur and automatically shut the engine down. At this time the Class 48's were covering the Liverpool Street - Norwich express service, I well remember investigating one of these failed locomotives at Norwich.

When these failures were brought to the makers attention, British Railways were advised that no other failures had been reported for the 12LVA engines. With the problem identified, rectification would have been relatively simple, with the engine out of service for perhaps twelve hours. However this modification was not carried out, when the failures occurred it then meant a Works visit requiring the removal of the power unit and the fitting of a new crankshaft and connecting rod as a minimum. If the failure was not too serious the shaft could be ground undersize and re-chromed, unfortunately the BR failures tended to be very bad, requiring a new crankshaft (cost GBP35,000). Although the Class 48's would run without the modification applied to the SNCF machines, the modification was carried out to HS4000 Kestrel during its visit to Vickers, Barrow in 1970.

When BR was considering withdrawing the Class 48's a long discussion took place with one of the power equipment engineer's at the Railway Technical Center, Derby. Considered an influential figure and a friend towards Sulzer, he earnestly wanted to keep the LVA24 in service, fully recognising that this would ultimately be the replacement for the 12LDA28C. There was much frustration with the situation when Sulzer advised that the problems were of BR's own making, that no further investigations were taking place and no other solutions were being considered. The investigating engineers sent by Winterthur to look into the failures were clearly looking to blame BR, and were apparently not prepared to accept any other answer. There was therefore little alternative but to withdraw the Class 48's.

Because the LVA series engines were the responsibility of Winterthur, not London, it was left to the Swiss engineers to research any issues with them. When a Swiss based engineer came out to Crewe Works to investigate a Class 48 engine failure during 1969 a small split in the lubricating oil filter element was discovered, this was then blamed for the bottom end failure. If the oil had been contaminated by the dirt it should have shown up in contamination of the other bearings, but none could be found.

On the SNCF engines the locating pin had been removed. Had this modification been carried out the LVA24 problems would not have occurred on BR and since the LVA24 was intended by the BRB to be the replacement of the LDA28C in the Class 47 at some future time (as seen in a letter in the CM&EE Dept, Derby), then traction history in Britain could have been very different.

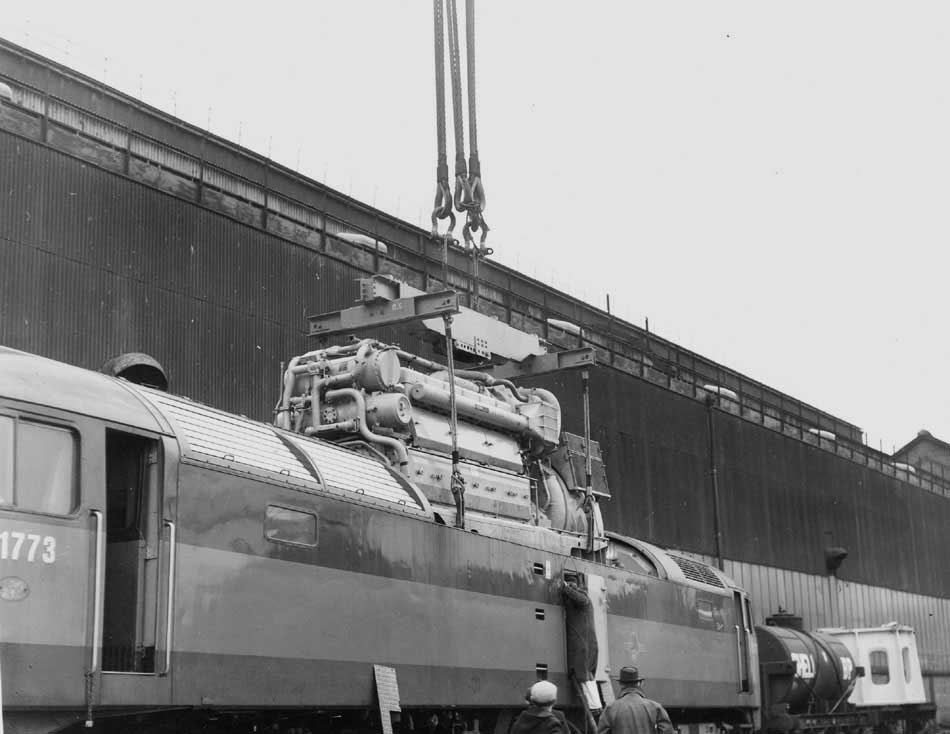

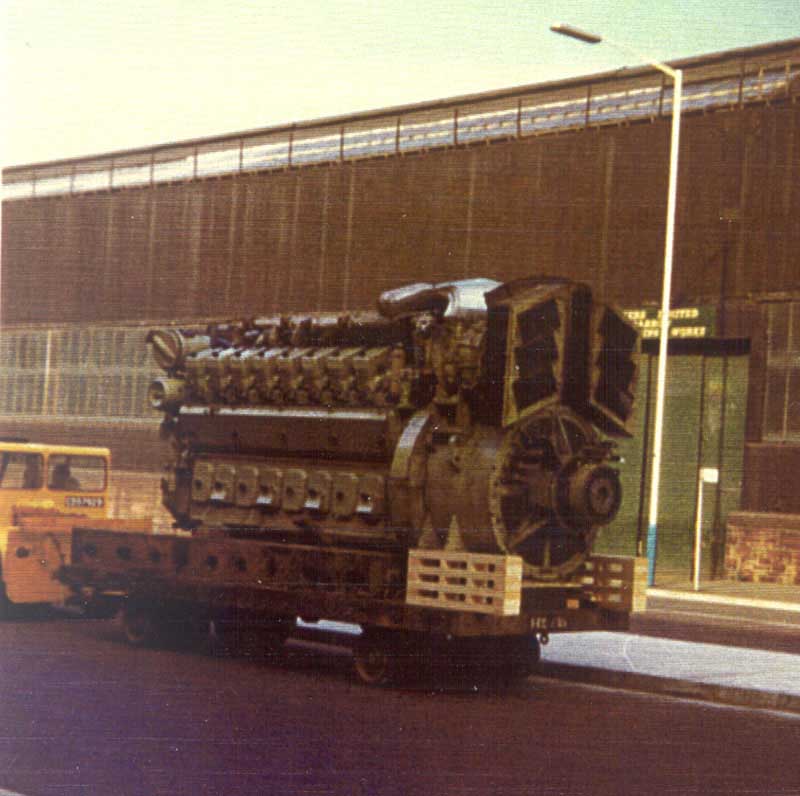

When the Class 48's returned to Tinsley I spent a little time with them. Visits were made to Crewe when the 12LVA24's were removed from the Class 48's, being returned to their makers, CCM in Mantes for further reuse on the SNCF.

The only other traction LVA24's, apart from those used in France and the UK, were exported to Cuba, interestingly these were Derby built locomotives since they were completed in the International Combustion factory situated alongside the Derby - Burton main line. I was not involved with these locomotives although ironically my wife at the time was secretary to the personnel manager at IC. Eventually visits were made to Cuba, but as a representative of Paxman assisting with their Brush built shunters powered by the Paxman 12YHXL. Inquiries made about the Cuban 12LVA's suggested they were laid up somewhere but it was not possible to check further on these visits.

LDA28

The LDA series engine was one of the most prolific on British Railways, with about 1,400 locomotives in service powered by the six, eight or twelve cylinder models. The first LDA's were constructed by Armstrong Whitworth during the early 1930's. The last were turned out by Electroputere, Craiova in the early 1990's.

The 12LDA was a 'double bank' engine - essentially two six cylinder engines placed side by side and driving the generator through a common output shaft. For Sulzer this concept had first been applied in two locomotives operating prior to World War Two, those built for use on British Railways should have been the highpoint of its development. Unfortunately it became entangled in a series of failures which would eventually require a costly repair programme.

All of the BR LDA28 engines had problems, the 12LDA28C version being the worst. Some were of a structural nature, being identified as assembly/welding defects. Others were down to the design rating, an ongoing problem was the cylinder head stud failures. These were fatigue failures due to the the flexing of the cylinder block top plate. Ironically when Freightliner derated their Class 47's to 2,400 bhp all the problems that we struggled with for years went away. The French 12LDA28s, rated at 2,000bhp did not suffer similar problems.

The cost of the rectification for the 12LDA28's came to about GBP4 million at the time. Because some of the problems were constructional about half of these costs were allocated to Vickers. The 12LDA28C's were not cheap, when new they cost about twice that of the English Electric 16CSVT.

During 1966 I was at Loughborough assisting with the rehabilitation of the Class 46's and the final delivery of the Brush built Class 47's. The upgrade to the Class 46's involved their electrical systems, controls and electrical machines. The engines were sent to Vickers for overhaul and included the incorporation of the most recent modifications.

Back in 1959 when the first 12LDA28's entered service on British Railways it was probably not envisaged that forty five years later a small fleet of locomotives powered by these engines would remain in revenue earning service. This longevity was obviously made possible by the previously mentioned major repair programmes in the 1960's and the skill and ingenuity of those at Derby and Crewe who, in the following decades, worked to minimise the known failings of these engines. The LDA28s gave fairly good service in terms of low wear rates on the running gear and usually the known structural problems did not cause line failures.

The railway workshops would develop repair procedures and had the resources to stay on top of the fractures in the engine frames etc. At Derby we became experts in the repair of welded structures. We would try one repair method and wait for the engine to return on its next overhaul to see if our repair had been successful. One of the ongoing problems were fractures in the top flange of the cylinder liners, caused by the flexing of the cylinder block top plate. When these were originally discovered the liner would be scrapped. However BR studied the failures and devised a system of predicting how far the fractures could propogate before the liner was unfit for service. In this way liners with fractures would be refitted in the knowledge that the liner would last to the next overhaul. It should be mentioned that the cylinder liners came from several different manufacturers, the 'grey iron' Winterthur liners were the best. When they failed their fracture propogation was very predictable, although these liners were twice the cost of the other equivalents. At works overhaul all the cylinder head studs would be ultrasonically checked - any with fractures would be changed. Sulzer continued to provide free technical back up long after any warranties had run out. As service engineers it was our job in the late 1970's to present the acceptable face of Sulzer. My role in particular on the LMR/ER was to liase with the CM&EE office in Nelson Street, the Railway Technical Center, Derby and Tinsley depot, so that any potential problems could be reported upon and that we were on hand to put forward the Sulzer viewpoint.

At the end of the 1960s Derby Works purchased fifty Mk II 12LDA cylinder blocks to feed into their engine overhaul programme, this step had been taken to mitigate some of the costs involved in repairing fractures on the cylinder blocks then in service. When approval was given in 1972 to equip fifty Class 45's with electric train heating equipment we had to plan the repairs so that these Mk II cylinder blocks found their way into the Class 45/1 locomotives. These new power units were much more substantial than the earlier blocks, being much more rigid and weighing some thirty percent more. The top deck & cross girders were thicker. The girder castings were shaped so that when welded to the top plate and the side walls, any stress raising notches and corners were minimised. The internal water pipe which caused so many problems when they fractured and leaked oil into the crankcase had been completely eliminated.

Whatever the shortcomings of the LDA28, BR learned of its limitations and developed repair procedures to keep them on the road. Very importantly they were able to repair them in-house, avoiding the need to send them back to the manufacturers. Discussions with management in the 1970's suggested that the LDA28 would remain in service probably until the end of the 1980's! For the 'A' & 'B' variants this was a reasonably accurate prediction. However although major inroads were made into the derated 'C' variants during the 1980's & 1990's many would continue to see service into the new millenium. And surprisingly some of the six cylinder variants in the Class 26's soldiered on into the 1990's, whilst the eight cylinder engine in the Class 33's continues to see service today in a small group of locomotives.

R Series Engine (R = Research)

From within Sulzer the opinion was that the 'R' engine was only built to prove that it was possible to design and build an LDA28 without all the problems associated with the earlier engines. The LDA28-R was listed as a six cylinder rated at 1,700bhp at 850rpm and an eight cylinder in line rated at 2,300bhp at 850rpm. The six cylinder engine was intended to be fitted into Class 25 D5299 as a test bed, but prior to this happening the decision was made in Winterthur to discontinue with traction development.

Only two six cylinder 'R' series engines were built. One went to Winterthur and was eventually scrapped there. The second, intended for D5299, remained at Vickers until about 1970 when it was sold to a North Wales scrap merchant. It was not immediately dismantled, later receiving a new lease on life following the industrial disputes that affected the electricity supplies during the early 1970's. It was purchased by Kays Mail Order to power a standby generator at their warehouse in Worcester.

The eight cyliner version of the 'R' engine was never built. It only existed on the drawing board and publicity brochures.

Nigeria

The engineers working for Sulzer UK could be expected to travel overseas from time to time in support of those locomotives sold through the UK offices. By the mid 1960's this was limited to Nigeria & Australia. I was fortunate to make two visits to Nigeria when working for Sulzer, the first trip was for three months, then a spell in the UK, then back to Nigeria for a further twelve months.

In the 1960's I was assigned to assist the Nigerian Railways, who at the time were operating 29 Station Class diesel electric locomotives built by Metro Cammell, Saltley, Birmingham. These were equipped with a Sulzer 6LDA28C 1,400 hp at 800rpm with AEI electrics. I had been present at the Metro Cammell works during the build of the later machines, installing and testing some of the engines. Looking back on this time, our gear was not that good. The Nigerians also operated fifty five General Motors built locomotives. These GM's were much more user friendly, particularly when it came to maintenance - on a GM unit you could change a piston and liner in two hours, on the Sulzer it took eight hours. On the GM all the brake pipes were on the outside of the frames with subsequent easy access. On the Sulzers most of the brake pipes had been installed during the building of the locomotive and were situated, most inconveniently above the traction motors.

Known as the 'Station Class' the 1400 series machines carried a factory painted name and crest on the cabside under the cab window. Names included Makurdi, Maidugeri, Ibadan, Enugu, Port Harcourt, Jos, Bauchi, Zaria, Kaduna, Sokoto, Katsina, Lagos & Zungeru.

One of the main problems encountered in Nigeria was the lack of tools and spare parts. The prinicipal difference between these engines and the 6LDA28B carried in the Class 25's was the fitting of larger intercoolers and a different cooling system to cope with that change. The Class 25's had an electric powered fan for cooling, the Nigerian locomotives had Serck Behr hydrostatic cooling fans and motors which were a constant nightmare to keep leak free. These engines suffered other failures similar to that of the Class 47's - structural failures, cracks, broken cylinder head studs, power take off for the compressor drive failures, high exhaust temperatures - it was a full time job to keep them in service.

(The hydrostatic cooling system had already given problems with BR's Class 46's, the earlier Class 45's had electric cooling fans. In the 46's & the later 47's the hydrostatic systems were pump driven from the free end of the engine, which to some extent required the cooling fan speed to be dependent on engine speed. Overheating might result after a prolonged period of high load followed by an easing of the engine speed and consequent lowering of the cooling fan speed. A prime example of this might be the WCML Class 47's operating north of Crewe, having crested Shap full power running was no longer required, the engine speed drops, as does the cooling fan speed. But the engine still maintained much residual heat and still required maximum cooling for awhile longer. It was frequent for the Class 47's to display a high water temperature alarm (+192F) in situations like this. In contrast, when leaving Derby Works by the south footbridge it would be common to look down and see a Class 45 arriving from Leicester after a hard run, the engine would now be at idle but the cooling fans would still be operating at a high enough speed, independently of the engine, to maintain engine temperature within limits.)

The locomotives were used on a seven hundred mile run from central Nigeria (where I was based) to the coast, the freight trains would take about a week to complete the journey, the crack expresses took about three to four days. The freight trains mostly carried agricultural produce, vital to the Nigerian economy, at this time Nigeria's large oil reserves still remained untapped. There still remained alot of steam power in use, including the River Class (built by Vulcan Foundry, North British or Henschel) and some Manchester built Beyer Garrets.

My initial contract here was for three months, then another for twelve months. The job was to instruct the locals in maintenance & repair and was based on the running shed at Zaria. Travel was often involved. If a locomotive broke down on the track and it was accessible by road we would drive in the car to fix it, otherwise a little four seater railcar would take us to the location of the stranded locomotive. Zaria contained a railway institute which amongst other things had facilities for playing tennis, badminton or swimming, a number of other clubs were frequented by other ex-patriots. Colonial traditions still lingered with the employment of locals to assist with cooking, cleaning and garden work. We ventured out further than perhaps most ex-pats did, getting about on the local 'Mammy Waggons', visiting the local market to obtain produce. When longer work breaks occurred it was off sightseeing in Kaduna, Kano or Jos.

After the time spent in Nigeria it was back to the UK to look after 'Kestrel'.

Three views of 1426 'Zungeru' at Zaria depot, this was one of the last batch (1426 - 1429, delivered in 1966). The gentlemen in front of 1426 are maintenance fitters, apart from the man with the hat on - he worked for the yard overseer helping to shunt wagons around the yard. The names of the fitters have slipped into history apart from two: back row right is Mr E. O. Aligbe, from Sapele and most likely a member of the Yuruba tribe. In the running shed his nickname was O'due (from 'Overdue') - he was nearly always late for the shift. Most of the fitters and administration staff spoke good English, the cleaners & greasers however tended to speak their own native language, which in Zaria was Hausa.

Back row, second from left is Mr Mallam Alhaji Fatika from the Hausa tribe. Fatika, as he was always called, owned a Honda 90 motorbike. This was frequently used to visit many of the small villages in the area, including visiting his family. Fatika's father, a fairly well-off businessman, owned six AGIP petrol stations. Fatika's father had four wives, his mother was the chief wife. Other adventures into the bush required crossing large rivers using little more than dugout canoes, these canoes also carried donkeys, which had no trouble in getting into the canoe and remaining almost motionless as the river crossing was made.

Flash-overs were fairly common on the Class, that is when arcing occured between the commutator brushes resulting in the scorching of the commutator bars. The less serious cases could be cleaned up and repaired in situ, the more serious ones would require the commutators to be skimmed by machine, accessing the commutators required the removal of the generator. A significant problem lay with the drive to one of the traction motor blowers, the auxiliary generator and excitor. The latter two machines were not integral with the main generator (as in BR practice), but hung on the outer case of the generator carcase, together with the traction motor blower. All were driven through the auxiliary drive gearbox on the end of the generator. Unfortunately the torsional vibration from the engine was transmitted down the armature shaft to the gearbox and in time stripped the teeth from the gears on the auxiliary machines, causing the disintegration of the traction motor blower impeller. A modification programme was instituted with all the gears changed for a resilient type which had rubber bushes between the centre boss and the tooth ring.

The last two ordered, 1428 & 1429 were equipped with dynamic brakes for use on the hilly district of Kafanchan on the Jos plateau. The rheostats were mounted in the hood roof. The brake was put into service from the engine speed controller by pushing it in the opposite direction to normal engine speed increase. A series of 'B's would appear on the display and the engine speed would increase to provide cooling air to the traction motors. It appears the dynamic brakes were seldom used.

Despite the operating problems encountered with the 'Station' class, in 1969 there was an enquiry from the Nigerian Railway Corp for another twelve, to be then followed by a further fifty six. The enquiry would also involve some sort of government financial aid package, this was initially not forthcoming from the British government. Hitachi stepped in with an eighteen year loan package for the first twelve & nothing to pay for the first five years. The British government countered with a slightly shorter loan package - of fourteen years. Too late, Hitachi got the first part of the order whilst the additional fifty six went to ALCO (MLW) under a Canadian Aid Package.

Attempts to revive the Class in the early 1980's by a company in Lagos did not succeed due to a lack of finance.

I returned to Nigeria in 1984 for Paxman, following up on the fifty four Brush shunters powered by the Paxman 8RPHXL engine, whilst there none of the 'Station' class were seen.

HS4000 'Kestrel"

During the early 1960's there had been a maximum of forty six Sulzer traction service engineers on British Railways, by 1967 when Kestrel came on the scene there were only four left and I was the only service engineer permanently assigned to 'Kestrel'. I would ride on the locomotive most days for over two years. There would usually be a service engineer from Brush in attendance as well. Any problems found in service would be rectified at Shirebrook or Tinsley. This might involve changing such components as the injectors or fuel pumps, to be ready for the next day's service. If the problem was of an electrical nature I would stay and assist the Brush service engineer. I looked after her like a baby, keeping the engine clean, ensuring there were no leaks. Happy Days!!

The HS4000 was a great machine, but only used to its full potential once during a six week period when it headed the non-stop 08.00am Kings Cross - Newcastle service & 16.45 return, which at that time was diagrammed for one of the Deltic fleet. On the first outing we knocked fourteen minutes off the Deltic timings. The locomotive rode well on its Class 47 accommodation bogies, the ride giving no noticeable difference when compared with its original bogies. After these passenger train adventures it was back to the mundane: the Hull - Stratford freightliner service & Shirebrook - Whitemoor coal traffic. From memory there were six to eight drivers trained on Kestrel at Shirebrook and probably a like number also at Hull & Stratford - the controls were similar to that of a Class 47. Then it was off to Russia, eventually to be scrapped there in 1993. An ignominious end for a promising project. After this no other company would consider such a private venture for BR.

Only five 16LVA24 engines were built. One was fitted in 'Kestrel', later scrapped in Russia. A second was the type test O.R.E. engine which was later scrapped at Oberwinterthur. The three remaining engines ended up at power stations, two at Schaffhausen, Switzerland, and one at Dunkirk, France - all as standby generators, and all still believed to be in service.

A direct descendant of the LVA range was the A/AS series introduced in 1969/1970 as marine generators and propulsion units. Design wise it was based on the LVA though its frame was cast rather than fabricated, being primarily intended for marine use it was suitably beefed up. For example the 12LVA24 weighed 14,400kg for a continuous rating of 2,650bhp at 1,050rpm, whilst the 12ASV25 weighed 18,900kg for a continuous rating of 3,000bhp at 900rpm. The ASV engines could also operate on heavy fuel.

Its a cloudy ??? as HS4000 Kestrel transitions dockside at Cardiff into a Russian freighter for a new career in the USSR. The ship was the MV Krasnokansk which ironically was powered by a Sulzer RD76 main engine!

At some point a Sulzer manager did visit Russia to assist HS4000 with some governor problems. During 1995 Geoff and the former Brush test bed foreman tried, through Sulzer Moscow, to see if the locomotive still existed, with the intent to try and bring it back to the UK. Unfortunately by the time of this request the locomotive had been scrapped.

The end of the Rail Traction business

Sulzer's first locomotive entered service in 1912, the company remained in the Traction business for over fifty years before concentrating on the Marine diesels. The reasons for the departure from the traction business include:

In a high level meeting with the BRB George Sulzer gave a commitment that 'the Sulzer engine will be put right, whatever the cost' - refering here to the 12LDA28C. The costs were high, the problems very significant, so much so that BR were considering re-engining the Class 47's with the Ruston 16RKC.

The bad experience with the 12LVA24 on BR in the Class 48.

The costly private venture with Brush on the 'Kestrel' locomotive which came to nothing. This project had developed from BR's desire in the 1960's to operate a fast mixed traffic locomotive. This requirement was later changed to slow freight locomotives and fast lightweight rolling stock, resulting in the Class 56 and the HST with no need for further development of 'Kestrel'.

In the lesser developed countries the early inroads made by Sulzer were not sustained, GM/EMD had tied up the market with simple cheap locomotives.

Outside of the traction business things were changing, not necessarily for the best. Sulzer had long been the leader in the marine engine world - now they were losing sales to B&W as fuel consumption became a major concern for ship operators. The days of the loop scavenged two stroke were drawing to a close, but Sulzer were finding this tough to swallow. Fortunately Sulzer faced the challenge and spent two years designing & developing their own uniflow scavenge engine, which became the RTA series.

Toubleshooting

After the loss of 'Kestrel' the few remaining service engineers had more or less a free hand in what they did. My patch included the LMR, WR & ER, based in Derby, moving here permanently in 1970. We had company cars so it was no problem to go out into the field to investigate problems. The resources of Derby Works and the BR Derby metallurgical laboratory were on hand to help, frequently calling in someone from the CM&EE department to assist. As long as a report of my activities was produced for Sulzer management all would be well.

During the early 1970's complaints started on the Southern about the smokey Class 33's, from this came a working party to look into this, later the investigation was enlarged to include the Class 47's. The investigation was known as the Black Smoke Working Party and was overseen by the BR Fuel Injection committee. Although this problem first surfaced on the Southern we on the LMR didn't consider them to be a proper railway for diesel operations! After all they barely had one hundred Sulzer engines in service, whilst we on the LMR had about 650 to look after!

The investigation ran for two years, most of the problems were related to the overhaul procedures at Derby and Crewe. Injector nozzles were being repaired when it would have been better to simply scrap them. However the vested interests in the workshops wanted to carry on their reconditioning, a sort of job creation scheme. Nozzle seats would be ground until the case hardening was ground right through. When such a nozzle went back into service it lasted about eight hours before leaking and dribbling.

It was proven in extensive load testing on a Class 24 at Reddish depot and later on the test rig at Derby that it was better to run them longer and then throw the injector nozzles away. A new injector nozzle would cost about GBP15.00. Nozzles would normally require overhaul between 1,500 & 2,000 hours. Nozzle problems would lead to high exhaust temperatures which could lead to turbocharger failures, valve failures and exhaust pipe problems. Other manufacturers engines also experienced problems, but revealed in different ways. For example the English Electric CSVT engines used to suffer from fuel dilution of the lubricating oil.

Other investigations related to problems affecting the engine timing and the set up of governors and fuel pumps - information gained in this fieldwork proved useful for my later work with the marine engines. Much time was also spent on dealing with the fractures occurring at various locations (cylinder blocks and crankcases) in the LDA28's. Although these did not normally cause failures in traffic they did require major works attention, some four years were spent off and on at Derby working with the CM&EE in tackling some of the repairs.

Investigations were carried out into why engines required oil changes. This involved a study of the oil histories of hundreds of Sulzer engines. The information gleaned from this study continues to have use today. Likewise a study was carried out into the life of lubricating oil filters and the influence of piston scraper ring band width on the running-in of engines.

At the end of 1976 I transferred to the Sulzer Marine Division, leaving Derby in 1977, moving south to the London area.

Onward!

When the Sulzer Traction department was being wound down in the UK I moved over to the Sulzer Marine Division and started a complete new episode in my life of marine engine technical service work, commissioning and sea trials. This included trips to the Hellenic Shipyards in Greece on commissioning work and to Porgsgrun, Norway for a guarantee dry docking on a Ro-Ro ship.

The downsizing and eventual closure of the Sulzer UK traction department sent the service engineers to many locations. Some stayed with Sulzer, like myself moving to their marine division across various parts of the globe. One stayed with Sulzer to become the Managing Director of Sulzer Nigeria. Others stayed in the engineering field but changed companies, one to General Electric in Vancouver, another to a power station in St Moritz. Some simply retired, whilst others are no longer with us, hopefully their experiences are recorded somewhere, about times & events now fast disappearing.

The first task handled in the marine division involved working with the Sulzer A25 (son of the LVA24), there are many thousands of these A25's in service as marine generators and propulsion units. The five cylinder version rated at 950bhp at 750rpm was the most common of this family. A three month stint in Winterthur allowed for training on the slow speed diesels and the Sulzer Z40 series. The easy going ways of the traction business were not mirrored in marine service. Problems would require travelling at short notice, making one's social calendar full of uncertainty. Whereas a failed locomotive could be swiftly replaced, a ship with motor trouble needed to sail no matter what. Big financial penalties and loss of goodwill meant marine service engineers needed great flexibility. It was not unusual to board a ship coming into the locks at Tilbury in the early hours, work all day on a problem, sail down the river to test the engine, then leave the ship with the pilot. This involved scrambling down the jacobs ladders whilst underway, and then jumping onto the moving deck of the pilot launch!

On the large marine engines most of the routine work, such as piston changes was carried out by the ship's staff. The Sulzer engineers normally only had involvement in the more complex problems such as bridge control systems, high liner wear, engine fuel pump timing, performance analysis etc. There was always someone onboard to help if required. Other work involved standing by at drydock, supervising overhauls and attending sea trials after docking. All ships had engine tools with a good range of general equipment socket spanners and the like, plus a small machine shop. I usually carried a vernier, small shifter, torch, feelers, setting gear for fuel pumps and small mirror.

I left Sulzer in 1979 to work for the service department at Paxman Diesels for seven years. This mostly involved looking after foreign navies.

As at 2005 I am still involved in Marine technical service work. Earlier this year I was supervising the overhaul in Belfast of an eight cylinder Sulzer marine engine producing 8,000bhp at 510rpm type ZA40S, once refitted it was off on twelve hour sea trials to Rosslare.

![]()

The well worn phrase that truth can be stranger than fiction certainly overtook your webmaster during 2008 whilst working on an article about the reminiscences of an ex British Railways driver on the LAMCO iron ore railway in Liberia. Whilst the article was a wonderful look into American style railroading in West Africa, the railway did not operate any Sulzer powered locomotives, but did own some ex British Railways Class 08 shunters and railcars. However shortly after completion of the article an email arrived concerning the possible export of at least two used locomotives from Romania to Liberia for use on the iron ore line which was to be reopened at some point. The email was asking for an evaluation to be made of the two locomotives, these were fitted with Sulzer six cylinder engines.

The request was forwarded to Geoff who was contracted to visit the two locomotives in Romania and carry out the necessary inspections. The view below shows Geoff (in red overalls) at the factory alongside a Mr Stoica and Faur built LDH125-472, now suitably refurbished. It is believed that at least two locomotives were shipped to Liberia, but the global recession in 2008 saw the planned restart of the mine operations put on hold.

When Geoff sent this photograph for inclusion on the webpage he remarked that it was in considerable contrast with the one at the top of this page, taken some forty years earlier!

With thanks to Geoff for sharing these experiences, hopefully more memories (& photographs) will be added as time permits. All errors and omissions belong to your webmaster!

![]()

2009

During June 2009 your webmaster made a return visit to England to celebrate some significant family birthdays and to put some faces to names that had been only email addresses until this trip. Geoff was gracious enough to drive up to Derby for a pub lunch and an afternoon of memories. It was a wonderful afternoon and long overdue after just over four years worth of emails between us. I wish the time spent together could have been longer, but it was not to be.

On his visit to Derby during June Geoff had mentioned his upcoming holiday to North Wales, he was looking forward very much to this trip especially to be able to spend time with Sally. I hope this photograph provides a way to close this story, regrettably I am sorry to advise that six days after the photograph was taken Geoff passed away suddenly.

A comment from a neighbour whilst Geoff was living in Derby "Some people pass by and make no mark but Geoff was the exception".

![]()

Page added May 22nd 2005.

Page updated October 24th 2009.