All black & white views are from BR publicity material, all other views are from the author's collection unless otherwise stated.

The first railway workshops built at Derby were in 1840, adjacent to the new railway station, then owned by the Midland Counties Railway, the North Midland Railway & the Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway. In 1844 these three companies amalgamated into the Midland Railway, establishing its Head Office and center of operations at Derby. The workshops site occupied 8 1/2 acres, of which 2 1/2 acres were covered. Expansion of the railways led to the separation of the Locomotive Works from the Carriage & Wagon Works in 1873.

In 1923 the Midland Railway was absorbed into the London Midland & Scottish Railway Company, which in turn became part of British Railways in 1948.

In 1963 the railway workshops were separated from the Regions, being headquartered at the Railway Technical Center, Derby.

A total of 2,937 steam locomotives were constructed at Derby between 1851 & 1957, whilst 1,010 diesel locomotives were constructed between 1932 & 1967. For the trainee entering Derby Works during the late 1970's the Works covered 51 acres, of which 13 were covered. Principal tasks included the repair and overhaul of diesel mainline & shunting locomotives, the reconditioning of diesel multiple unit engines & transmission equipment, and the overhaul of breakdown cranes and track maintenance vehicles.

A pamphlet issued by Derby Works (at least during the 1970's) featured the final diesel built at Derby on the cover, with a tour map and description of the various shops/buildings within the Works,

The following notes are recollections from a former BREL employee who worked at the Locomotive Works from 1976 to 1982, starting as an apprentice in the training school, passing out as a millwright based in 1 Shop. The term 'Millright' stems from the start of the Industrial Revolution, when the earliest of the machines required repairing/maintaining, a millright would be employed.

Introduction

In July 1976, school life came to an end. In six weeks, after the holidays, I was to become an apprentice at BREL Derby Locomotive Works. A daunting prospect - into the big wide world, and a leap into adulthood. This may seem a bit of a surprise to the youngsters of today, but the position was the first I'd applied for, and after the interview and medical, was told to report to the works the following September. The works at this time took on over one hundred apprentices a year, but with a staff of well over 2,500, the many retirements and job movements had to be catered for. As an apprentice you were taken on as "if you knew nothing", and from whatever background or education, you were taught all that was required, to become fully skilled in your chosen trade.

The apprenticeship was split in basically two parts. Part one was a year in the works training school, first learning all aspects of engineering in the school's specialised "sections". During the latter part of this year, you were allowed to choose the trade you would eventually become fully skilled in, from those available. This was followed by three years "on the job" training, visiting various locations around the works gaining hands on experience of your future life ahead. For all of the four years, academic education was provided from the then Normanton Road, Willmorton, or Kedleston Road (now Derby University) colleges, using block or day release courses at various times of the years.

The training school on that first day seemed a huge building, not unlike something you had left just six weeks earlier at school. This early time in many ways paralleled the school life we had just left. All the instructors were to be called "Sir" or Mr., followed by their respective surnames. Work times were strictly adhered to, and no form of tomfoolery was permitted in the school at any time. The floor was immaculately painted and lined out. The only concession we seemed to have, perhaps as a sign of impending adulthood, was the opportunity to smoke in the cloakroom.

The works training school as seen from the "top" end. Fitting 1 section is to the right of the foreground, whilst the Fabrication section is to the left. The large rectangular panels on the walls are steam radiators, which were supplied by the works power station. Of note is the number "100" on the base of the bench in the right foreground. The time recording clock for the school was situated under the wall clock in the far distance. We all had to line up, in clock number order, before leaving time, the number being a guide as to where the 100th person should be standing!

The building was located between the main offices and 4 Shop, and was, on paper, 3 Shop, but this form of identification was rarely used. Located at the front of the training school was a general office, usually staffed by three people dealing with the general day to day running of the school. Opposite, was a display area, which had on show the numerous cups and certificates awarded through its history. Behind this area, and with its door located in the foyer was the head of the training schools' office. Once inside this room, a large well placed window overlooked the main body of the school. Returning to the foyer, a corridor ran off to the left, behind the general office, and led to the trainees cloakroom, which can only be described as looking like a 1950's school version, with long racks of pegs, bench type seating underneath, and wire rack sections beneath these, for the storage of bags etc. A tea urn was located in the corner of this room. The cloakroom was directly linked to a washroom and toilets behind. Also off this corridor, led a staircase, to two classrooms on the first floor.

The main body of the school was a huge area divided by a walkway directly down the centre. It was split into five sections, each giving specific learning about a particular trade. Each section held its own tools, neatly positioned on their shadowboards. Blackboards adorned the walls, and where needed, individual benches placed in perfect rows, were bolted to the ground. A dedicated instructor was also assigned to each. Having walked into the school, the first two sections were Fitting 1 to your right, and Fitting 2, to the left. Continuing down the central walkway, the entire right hand side was then occupied by the Machining section. To the left centre was Fabrication, and finally in the bottom left hand corner was the Electrical section.

As said before, each section began its education from the basics. Fitting meant fitting, and not fitting "with machining for the difficult parts". Each exercise was broken down into basic sub-exercises, learning the precise art of all the tools used. The end product would nearly always be a hand built engineering tool that could be purchased and placed in your new toolbox.

Update - according to Tim Moore this view was taken during 1967 when Ben Read was superintendent of the school, Mr Wheeler was in charge of fitting and still present was 'Noddy Churchman'. Identified in the photograph are Brian King (front left), Tim Moore (dead center) and Peter Wheatley (front right). Tim adds that his apprenticship time was happier than the proverbial schooldays - Tim left Derby Loco in 1971 for the marine life, as an engineer supporting steam turbines in cargo ships.

One example of an exercise on the fitting section, was the making of a pipe vice. Production started with a rectangular piece of steel, some six inches by four inches and nearly one inch thick. Stage one saw the block filed flat and square along its edges, not an easy task for a fully qualified fitter, let alone a raw sixteen year old. But not only flat and square - surface texture was also measured against comparators, learning the art of producing different degrees of surface finish. The block continued to be worked on, secondly by cutting it into a 'u' shape by use of a hacksaw, again not an easy task, cutting two five inch slots in one inch thick steel. The central section was then removed by drilling a series of holes at the base, and chiselling out the unwanted piece. And the art of using a hammer and chisel was not for the feint hearted! A large safety cage neatly fitted over your bench, and with the work gripped tightly in the vice, the idea was, you attempted to have the head of the hammer make contact with the end of the chisel. The screams and yells of all those trainees who missed (including myself) confirmed the hammer frequently made contact with the back of ones hands or knuckles, a memory that will remain with me for the rest of my life! The tool continued to take shape, again filing and shaping the two jaws, this time learning the art of "case hardening" using a furnace and quenching in different liquids. Drilling and tapping the top for the screw saw the tool to completion.

It was during this time, that the training school was commissioned to produce a scale model of an APT-P power car ( I presume for promotional work). The actual full size versions were in production at this time in the works' 7 Shop. A model driving trailer and coach were going to be produced by our counterparts at the Carriage and Wagon, Litchurch Lane, works. Copies of the full size machine's drawings were given to the school, and for the model, everything was just scaled down. Several trainees commenced work carefully filing, machining and fabricating the body right down to the last detail. Several months were spent on this project, the final result being a great credit to all involved. The finished model was about three foot long. (As a footnote, I don't recall seeing this model power car ever again, but, to my delight, some twenty years later pictures of it turned up on the APT preservationists website, which can be found at www.apt-p.com/aptindex.htm go to www.apt.com/APTModels.htm. The model itself, is the one depicted in full InterCityAPT livery).

Similar basic knowledge was learned in all the other sections, from screwcutting on a lathe in the machining section, cold riveting, bending and forming in the fabrication section to machine and loom wiring in the electrical section. One memorable occasion during this first year was 'Parents Evening'. Imagine this today, if your parents were given a whole evening with you, at your first place of work! But in the mid 1970's it was still common practice for large firms to issue "indenture" forms. This was a written, binding document, whereby your parents consented to a firm teaching you a particular trade. The school that evening was laid out in style, with completed projects proudly displayed with our names below!

An additional building was also used by the Training School. This was the Welding Training School situated at the end of the bottom yard, next to Spike Island. Mainly used by the trainees in their specialisation period (for entry into 18 Shop), a week was spent here whilst in the Fabrication Section. This introduced us to the fine art of gas & electric welding, generally a first for most of us. I always said that if you got the hang of electric welding in that first hour then you were set up for the rest of your life. Twenty five years later I still cannot electric weld.......

Use was also made of 25 Shop. During specialisation in the Fitting sections a couple of trainees spent a week at a time filing and fitting rocker arms to rocker shafts. This was a nervous time for all of us as this was to be our first ever time spent in the actual Works. But after those first few hours it was a delight to be free of the constraints of the Training School, to be doing some proper work for a change!.

Mention must be made of those dreaded green overalls. All the Works wore navy blue bib & brace or boiler suit type overalls. The trainees did not, they wore green, for all four years of their apprenticeship. This had the disadvantage of making you stand out like a sore thumb for all the right & wrong reasons. Whenever a bit of lifting, carrying, tea making etc was called for, the first set of green overalls was selected. It also made the art of numbertaking in the Works somewhat of a hazard, as being spotted in the wrong place at the wrong time had to be explained. By taking a clipboard and pen around with me irate supervisors were placated when advised I was making notes for my training logbook!

In the latter part of the year, we all got the opportunity to select our chosen trade from those available, and from there on led to a period of "specialisation". This is where you were moved to the particular section that catered for your future career, and basic skills were replaced with a more in depth form of training. This would prepare us for that big outside world that lay ahead. In retrospect, my year in the training school, is one of fond memories. We were brought up on the basic skills which, in the twenty first century, seem to be rapidly in decline. So much is seen today (I still work as an engineering fitter), of young engineers, who are taught the cheapest and quickest way to overcome a problem - and it seems sad to hear from a teenager that he didn't realise there was a right and wrong way to fit a hacksaw blade. Perhaps, nearly thirty years on, things have changed, production methods are different, and things are taken for granted. Or, perhaps, just too much is done for us.

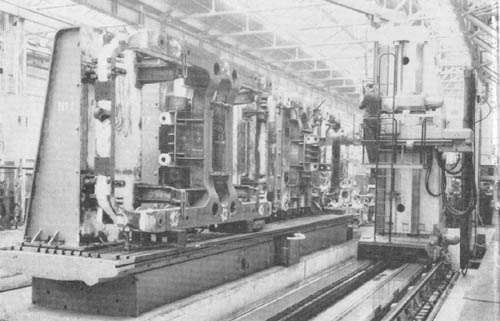

The size of some of the locomotive components required some formidable looking machines to fabricate & repair these parts. Naturally the machines themselves required regular maintenance from the millwrights to keep them in good working order. Seen here is a boring machine, used in the fabrication of bogie frames, a task that continued long after locomotive construction ceased at Derby Works.

The various Works departments would supply a list of their apprentice requirements for the following year. Back in the school, it was left purely up to us to decide which trade we would enter, within the limits of the Works requirements. If I remember correctly there were only five vacancies for Millrights that year, so I considered myself very lucky to have been chosen in that trade.

1 Shop - home of the Maintenance Teams - The Unsung Heroes?

Hundreds, if not thousands, of books have been written over the years, dealing with all aspects of locomotive depots and workshops. To the enthusiast, the locomotives, their backgrounds, liveries and diagrams seems to be of prime importance, whilst the role of the men who kept these buildings and their equipment in good repair, has been little documented. Has anyone ever given a second thought that the welding machine being used to repair a locomotive might itself, one day, break down? And not only welding machines - lathes, milling machines, cranes, and even down to that kettle in the canteen!

Derby Locomotive Works prided itself on its self sufficiency, and indeed, did not need to rely on any outside help for the running of its workshops. Although the maintenance staff possibly numbered the least amount of employees at the works they certainly provided a sterling service to be proud of.

The central base for the maintenance department at the works was 1 or Millwrights shop. From here various other departments, located throughout the works, specialised in their own particular form of the trade, all vitally necessary to keep the plant in full working order.

1 Shop itself was one of the original 1840's Midland Railway buildings, and served as the maintenance shop for the general upkeep of the works.The majority of the work was concerned with keeping the shops many overhead electric cranes in good working order, but virtually any general repair to anything over the Works 51 acres, was accomodated. This ranged from roofing work on 18 Shop, to a simple bench vice in 25 Shop! The main body of the building consisted of fitters benches situated along one side, a general 'work in progress' storage area, covered by an electric overhead crane in the centre, and the rest occupied by various machine tools. Each fully qualified fitter had his own dedicated 'mate', and at various times an apprentice was allocated to them. Fitter and mate worked as a team, and went as a pair on every job, no matter how big or small. A different team of fitters operated a night shift, thus covering a full 24 hours for the works. The machinists, with their own separate chargehand, provided any machined parts the fitters required to complete a repair. At the head of the shop was a small stores 'office' which issued drills and other small equipment to the workforce. To the side was the shops general office, with the foreman and supervisors offices behind. A door at the bottom of 1 Shop led to the Plumbers Shop, again with a dedicated team of employees responsible for the hundreds of miles of pipework associated with the works. The workshop also boasted a unique balcony, its floor built from wooden railway sleepers supported on ornate cast iron pillars. Access was gained to this floor, by yet again, a unique cast iron spiral staircase, or alternately, an outside stairway situated at the bottom of the shop, although this must have been added at a recent time due to fire regulations. This upper floor housed a number of small specialised maintenance sections, the larger of which dealt with numerous leather and synthetic components, both for the Loco Works and its sister, the Carriage Works. Alongside, a small cabin was the home to the Works Clockmaker, or in reality, clock repair man. As well as the numerous time recording clocks, the works at this time was still hoast to many early 20th century wallclocks, and all were kept to the second by this remarkable man. In latter years the clocks in the then new HST power cars became his responsibility, and were the first things to be removed on the cars entering the works, due to them being "Collectors Items".

The HST clocks were mounted on the driver's desk and were self contained items, not wired into the locomotive at all. They were analog 'wind-up' clocks that would be wound up as part of the regular servicing routine for the power cars. The clocks were only held in place by four bolts so when power cars came on Works the clocks were quickly removed for servicing and safekeeping by the clocksmith. On one occasion the clocksmith was not available to install a clock so our intrepid millwright was detailed to fit a finished clock in a power car located by the Test House. Whilst bolting in the timepiece a large clunk was felt followed by motion! The Work's Class 08 had buffered up & coupled to the power car, swiftly heading off to Etches Park. Finishing the job off en-route to Etches Park, followed by a good walk back, with tools to the Works!

On the opposite side of the balcony were two enclosed workshops, one repairing and servicing all the plants small hydraulic items (jacks, pumps etc.), and the other offering the same service for the works hand power tools. The remaining bottom area, serviced and repaired all the London Midland Region's oxygen/acetelene equipment, from gauges to gas welding equipment for small depots, through to large hand held gas cutting gear for the track gangs.All equipment that was moved to and from the balcony, was done so by use of a gantry hoist located next to the hydraulic section. (As a footnote, the terms 'top of' and 'bottom of' 1 Shop were actual expressions used. In geographical terms, the top of 1 Shop was at the Derby Station end, the bottom being the works canteen end.)

Moving out of the main doors of 1 Shop and, located on the other side of 'the slope' (again an actual term used, refering to the sloped walkway between the top and bottom yards), were the Chain Stores. In this small building, adjoining the General Stores, a staff of two kept all the works chains, slings and strops in good repair. (A strop was a sling made of flat webbed polyester, rope was the original material, due to inconsistences with the natural fibres of rope it was difficult to establish uniform safe working loads. The newer polyester material was much more easily rated, the different colours of the strops indicating the rating.) Of historical note, all the slings used at these times were made of natural rope, produced to order by the Chain Stores. The all but forgotton art of 'splicing' (joining) the two ends of these slings was common practice and these two gentlemen could produce you a sling of any desired thickness or length. Of interest is the fact that the rope used had three of its weaves coloured (red, green and blue), purely for the reason of being identified, if it was found to be used towing a failed car around the Derbyshire countryside!

Situated on the bottom yard, between the canteen and the Siddals Road gatehouse was the works garage. Derby Locomotive Works ran a sizable internal road fleet consisting of one man tractor units. All painted 'loco front end yellow', these little units moved the considerable amounts of locomotive components around the works, on trailers, to their respective repair shops. The works garage undertook any repairs needed to these units, and looked after their daily maintenance and running. Again, very little external help was needed, and often fully stripped down engines could be viewed. For emergency repairs out in the works, and an occasional tow back to the garage for more serious work, the department ran its own little four wheeler - this time an open top, two man, flat back unit, affectionately known as 'The Flea'. In a separate building, close by, behind the gatehouse, was the garage for the staff cars, and the departments office.This office was also the base for the Managing Director's chauffeur.

A walk, this time, along the bottom yard and into the works, saw 1 Shops electrical maintenance department, located in the first bay of the large 18 Shop complex. Unlike today, a multiskilled workforce was virtually unheard of in the mid to late 1970's. This being the reason for the electricians having a seperate building to the fitters. Both jobs were seen as different trades, and a fitter requiring a motor removed from a machine, had to call upon an electrician to disconnect it. And much to the annoyance of the fitters, if the electrician had to work on a motor, the fitters had to remove it! Their department, due to the 'smaller' nature of the work, was not as big as the main 1 Shop and was mainly taken up with benches, and specilised electrical maintenance machinery.

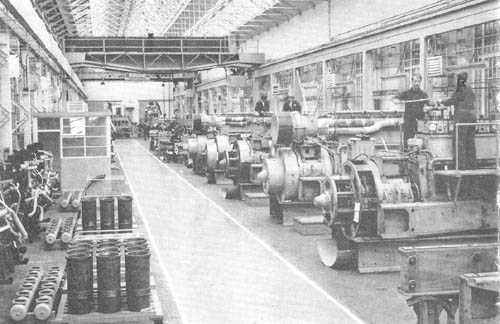

In this view of a rather neat and tidy shop used for overhauling the power units can also be seen one of the overhead cranes needed to move the power units around the shop. Derby was responsible for overhauling two of the bigger power units on BR, the Sulzer 12LDA28A & B and the English Electric 16SVT.

Continuing our walk down the bottom yard, and on coming to the Smiths/ Tinsmiths buildings end, on the left, a left hand turn brought the impressive Power Station into view. Situated virtually on the banks of the River Derwent, from which it drew its water, its primary function was to heat the Works. The building was manned continuously, having four large coal fired boilers, fuel was supplied by BR wagons via a siding that ran down through the Spike to the rear of the Tinsmiths. On a floor above the boilers stood the generator hall, containing two large generators to supply the national grid. During the winter months the works steam heating system became very visible. Leaking pipes and discharging steam traps (a device to remove condensed water from the pipes, normally situated at the lowest parts of the system) made the Works, on a dark evening in December, looked like something from a seedy Hollywood movie. And at quiet times the steam traps, discharging their water at irregular intervals sounded like several coffee makers all coming to the boil at once! Today (October 2002) a reminder of this once great central heating system can still be seen from the Pride Park road - the severed overhead pipes still connect the derelict 1 Shop plumbers to the General Stores.

Back to the bottom yard, and in one corner of the large outside storage area at the end of 18 Shop, stood a small building that even some of the works employees never knew about. It was here that the works fire extinguishers were checked, serviced, and refilled. As well as catering for the works, this tiny department provided the same service for the locomotive's fire fighting equipment, that were on works at the time. Although I am not sure of the fact, I believe that this department was not staffed at all times, and only on an 'as required' basis. A couple of fitters from 1 Shop were sent, as needed, to perform its duties. For the 'Home Brewers' amongst us, you could get your CO2 gas cylinder refilled here, in return for a donation to the railways patron charity - St.Christophers!

Into the main body of the works, and sited opposite the Locomotive Stores, 9 Shop Millwrights carried the maintenance departments second heaviest workload, although the shop itself was tiny in comparison. 9 Shop Millwrights carried the workload for all the machine tools in the factory. This form of maintenance was indeed very specialised, and the ten or so fitters in this department had to be skilled in a wide range of activities, from the mounting of grinding wheels to the removal of gearboxes in the heavy machinery. Every machine tool on the works was also subject to a planned maintenance system, and in these early times, the ease and versitility of a computer programme to handle this vast project, just hadn't been invented! Each piece of plant had its own service record written on a document that resembled a postcard. It was during the works lunch time, when all was quiet, that two or three fitters took the cards for about half a dozen machines, and on arrival at the said plant, gave a quick examination, rectified any small faults, and recorded the larger ones for attention at a later date. As a lunch time had been 'worked', the fitters involved, were allowed to leave half an hour earlier at the end of the working day. As with 1 Shop, a night shift was also provided, but unlike the main shop, the daytime fitters took it in turns on a weekly basis, to cover these hours.

And so concludes our tour of the Maintenance Departments at Derby Locomotive Works. Although the works as a whole indirectly kept itself running, any skill from any of the shops could be called on to help the departments out. 14 (Pattern) Shop often lent their woodworking trade to any office alterations, and 18 Shop would often effect a welded repair as required. The paint shops staff, were again used as and where required throughout the works. On paper, the Roundhouse was part of 1 Shop, and indeed came under the same foremen and supervisors, but this historic part of the works played no part in the maintenance of the plant.

Happily, 1 Shop, 1 Shop Plummers, and the Roundhouse survive today, and now enjoy listed status, although their future use, is still at this time, uncertain. It seems ironic today, that the only buildings still left standing of the once proud Derby Locomotive Works, are the ones that kept all the others in good repair. A fitting memorial to all the Millwrights throughout the works history.

As mentioned earlier tasks would befall the apprentices that no one else would want to do, or that might assist the apprentices in their skills. The arrival of 832 at Derby Works eventually led to the apprentices assisting in its repaint during 1980.

Crane Shop

The lads in the Crane Shop (roundhouse) were notorious in every respect - did grown men really avoid the place for fear of spending a couple hours suspended from a 76 tonner?

The test area for the cranes was directly opposite platform six, the newly converted diesel-hydraulic cranes were fitted with a tannoy system so the driver/operator could pass on instructions to the gang operating outside. On one fateful day the gang slewed the crane in the direction of Derby station, and announced that the next arrival at Platform Six had been changed to Platform Four, watching with delight as a stream of passengers shuffled across the platform!

As an apprentice in the roundhouse onetime a 76 tonner was taken up to the Spike and used to lift an engineless scrap Class 20. The reason for this manouevre is long forgotten, but was presumably a test of the crane's systems.

4 Shop

4 Shop was home to the master timeclock that governed all the other timeclocks spread throughout the Works. The master was clockwork, all others were electric. Should any break down, or have to be taken out of service or if the Works suffered a power interruption, the master clockwork one would within a few hours bring them all to 'right-time'.

7, 8 & 9 Shop

One of the largest of the buildings on the Works housed three shops, 7, 8 & 9 shop. Of these it was perhaps 8 Shop that was of the most interest to the visitor as this Shop housed the locomotives undergoing repair & overhaul.

In one instance a 7 Shop fitter was expecting delivery of a very large machine tool. We received a phone call in the morning informing us that the lorry with the new machine had arrived at the Deadmans Lane entrance, but was apparently four inches too high to clear the overbridge. After much scratching of heads the simple solution of letting air out of the trailer tyres provided just enough room for the whole ensemble to pass under the bridge.

For the locomotives access to 8 Shop was via a traverser. A tiny little one man tractor equipped with a large flat plate on the front buffered up to the locomotive being moved, shoving it slowly on/off the traverser. If I remember right the little machine was nicknamed 'Thunderbird 1'. It was a four wheeled, one man operated vehicle steered by two brake levers, one each either side of the driver's seat. Occasionally overzealous 8 Shop fitters could be seen to turn the vehicle within its own length by getting up enough speed then tugging hard on one brake lever. The little machine would lurch up in the air on one side, spin through 180 degrees, ready for its next job at moving a 130 ton locomotive.

The toolroom bay of 9 Shop held a secret that few people knew about. Underneath it were numerous longitudinal vaults accessed by trapdoors at the eastern end. Afew of these vaults were crudely lit, others remained in total darkness. Inside these vaults were racks running the entire length of 9 Shop, the shelves crammed full of jigs, fixtures and fittings for various builds of steam locomotives. On various occasions, armed with a torch, visits were made to these vaults, it was possible to pick up an item, blow off all the years of dust and find it neatly labelled or stamped with a number, as if waiting for its next time to be used on the shop floor above.

Bordering 9 Shop, Bogie Shop and Pattern (14) Shop were the Locomotive Stores, perhaps not the most accurate name for stores which seemed to supply little for the locomotives. But it did contain an interesting section known to most as the 'Golden Mile'. The racks in this area were completely sealed off with wire mesh, both down the sides and over the top, it contained all the little things in life that were useful! Padlocks, spanners, sockets, ratchets, drills - a veritable B&Q. Getting a requisition for something in the 'Golden Mile' was a fitters dream, as more often than not the storeman, who was not engineeringly wired up, would take you into the Mile to show him what you meant. This would be a chance to 'slip' things into your pockets, what was purloined didn't really matter, when one's pockets were emptied upon returning to the shop the items from the 'lucky dip' would soon find a use at the workbench.

Spike Island

During my time at works the scrapping at Spike Island was done by two men from 18 (Boiler) Shop. Their names escape me, but picture the scene, these two men, a plater and his mate were detailed to Spike every time a scrapper was moved to the site. Their 'home' for nine hours a day was a grounded wagon. After about one hour of being kitted out and working with oxy-acetylene cutting gear they very much became part of the landscape of dirt, oil, smoke and flame.

The plater was only there for the money, his mate seemed only focused on the scrapping of whatever ended up in his part of the world, be it locomotives or shop machinery. He was over six feet tall, with the weight to match, once kitted out in his protective leathers and carrying the torches and hoses, he seemed more suited to a role in a 'Terminator' movie. Permanently connected to a bottle of oxygen & acetylene one didn't mess with this chap. He was a man of few words, who seemed happiest when pieces of steel were falling of locomotives. And to the annoyance of the senior plater he had a weakness. When a new scrapper arrived he would leave his former creation (no matter what state it was in) and set about working on his latest art form! I remember vividly standing next to that plater, with him saying "look at him, he's like a kid with a new toy!"

Works Canteen

The Works Canteen was in fact two canteens. The kitchen area ran down the middle of the building, to the right were the dining facilities for the foremen & supervisors (but not the chargehands), whilst the area to the left was for the other workers. A morning break service was provided. At about 9am half a dozen or so trolleys would be dispatched to various parts of the Works selling sandwiches, bacon rolls, crisps, chocolate etc, though the bacon sandwiches were usually cold by the time they reached their destination, but were often warmed up by placing them on top of the tea urn for five minutes or so.

On Saturday mornings when the Works canteen was not open the various Shops would send their representatives over to the drivers canteen situated at the front of the former 4 shed for their excellent breakfast sandwiches.

Other snippets

A new airpipe was installed across the roadway next to 14 Shop, the boys in the paintshop spent a couple of days producing a chevroned board to hang below it to warn high vehicles. However their foreman who sanctioned the work overlooked one small detail. Both entrances to Derby Works (Siddals Road & Deadmans Lane) used underpasses that were both lower than the newly installed airline, the likelihood of any Works traffic hitting the airline was extremely remote!

Many people often asked questions about the mysterious start and finish times at the Works. The 8.07 start and 16.23 finish were a religious development from the very early years. In order for the devoutly religious amongst the workforce to start and end their work day with prayer, seven minutes were allowed before the 'clock' started/stopped.

During 1978 the weather vane on the top of the clock tower (clearly visible from the station) was removed for cleaning and painting. This was a very rare event and whilst on the ground it revealed its quite considerable size, well over six feet long.

The Works also boasted its own 'paper shop'. This was housed in a large garden shed modified with a front hatch, strategically located in front of the gatehouse by the main car park. A full selection of the 'dailies' could be purchased along with various magazines & periodicals. For evening readers the Derby Evening Telegraph was available when the day shift ended.

Requiem

Early in 1998 Derby City Council held an 'open day' to view the listed remains of the Locomotive Works. Much demolition had already taken place whilst the expected re-development had not yet begun. I returned to where the Training School once stood. Only a small area of the floor remained, the once gleaming paintwork now badly flaking. And in the concrete were sets of four holes, all neatly in rows where the fitting benches once stood........

For a plan of Derby Works circa 1980 go here

Page added November 29th 2002

Minor caption update March 26th 2005