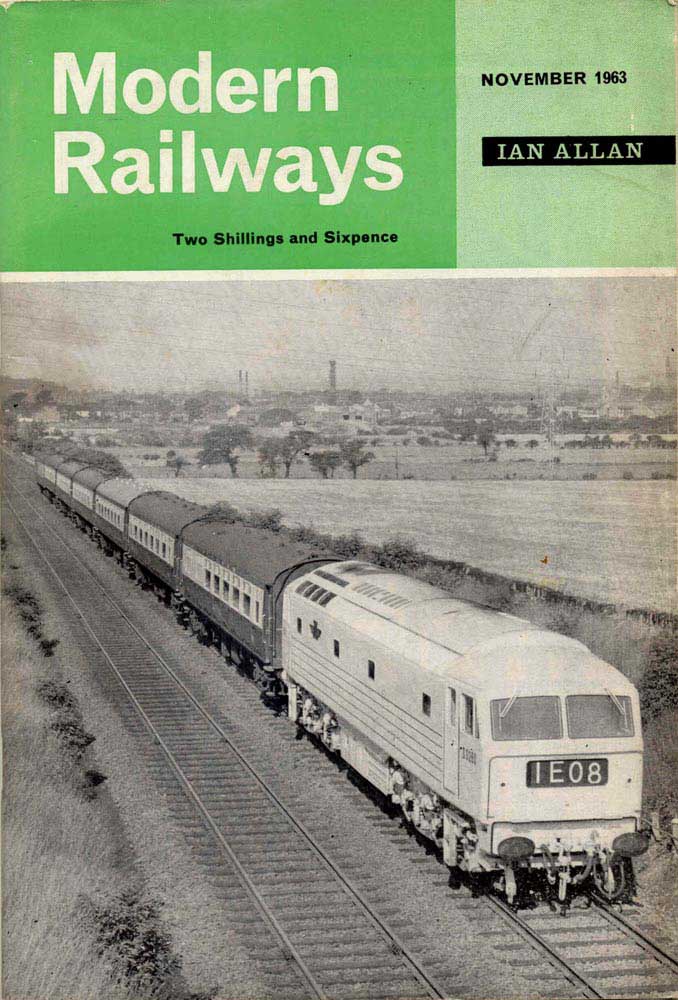

The unmistakable lines and livery of D0260 Lion are captured in a publicity photograph of the locomotive in the Smethwick yard of BRCW. In service the white livery presented a very smart image, it certainly could not be confused with any other diesels. However it would quickly gain a weathered look with the vagaries of the English climate. The stylish nameplate almost has an art-deco look to it, being inscribed with the names of the sponsers - BRCW, Sulzer & AEI.

![]()

With regard to the installation of Sulzer engines in diesel locomotive, the firm of Birmingham Railway Carriage & Wagon Co.Ltd, Smethwick probably holds a unique place in history in that all its diesel locomotives were powered by Sulzer engines. A total of 260 diesel locomotives were built at the Smethwick plant, and with one exception all the types had long and profitable careers in several parts of the world.

The Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company (BRC&W) had its roots in the Industrial Revolution of Victorian England, getting its start after a group of Birmingham businessmen recognised the potential growth of the railways and the need for the building and hiring of rolling stock. The new business, The Birmingham Wagon Co Ltd, started in 1854 by sub-contracting the work to a business based at Saltley. After ten years growth a 10 acre plot was obtained at Middlemore Road, Smethwick, to allow the company to build a works and construct its own wagons. In 1878 the company name was changed to include 'Railway Carriage', in recognition of it having built carriages and tram cars since 1876. Expansion took place with the Works eventually occuping a total of 56 acres. Whilst well known globally for its supply of railway rolling stock, the company also produced trolleybuses, buses, and for the military produced gliders, bombers and tanks.

In 1963 the Works closed with the site being redeveloped as the Middlemore Industrial Estate, opened in 1966. The parent company became the First National Finance Corporation Ltd. in 1965.

Diesel locomotives

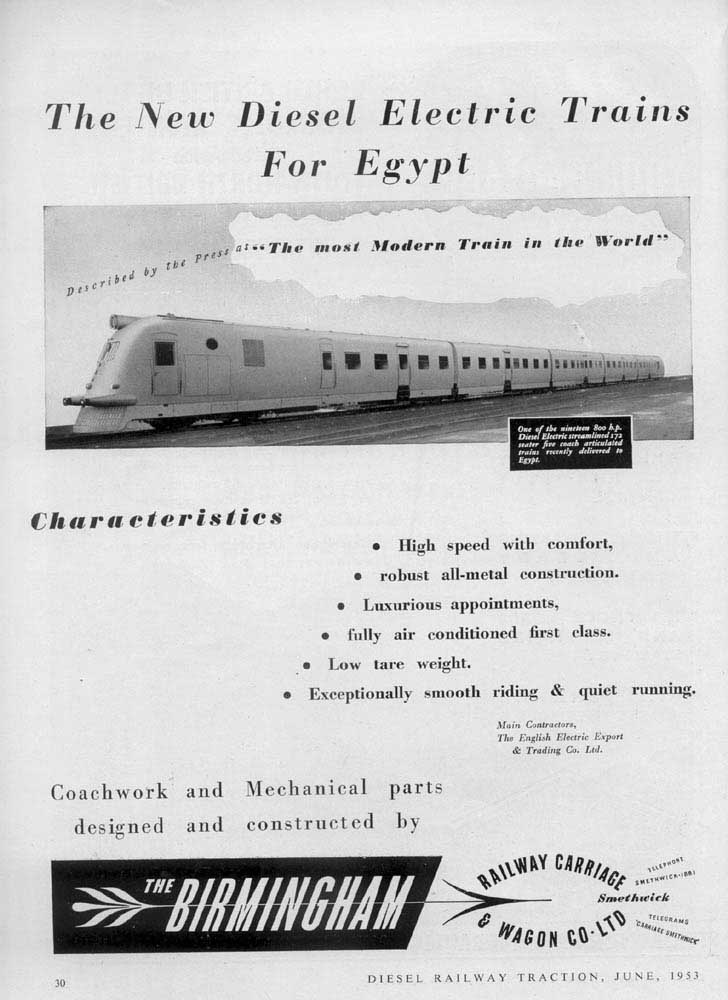

The first diesel locomotives built by BRCW were fourteen narrow gauge locomotives for delivery to the Commonwealth Railways in Australia in 1953/54.

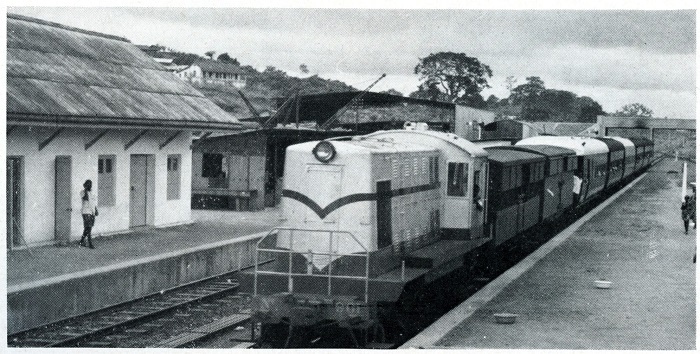

Six similar machines were built in 1954 (5) & 1962 (1) for the Sierra Leone Development Corporation, Sierra Leone.

Two years later and a little closer to home twelve locomotives were built for the Córas Iompair Éireann (CIE) in 1956–1957.

BRCW were able to gain orders from the 1955 British Railways Modernisation Plan, building a total of 214 similar locomotives;

47 1,160hp Class 26 in 1958–1959

69 1,250hp Class 27 in 1961–1962

98 1,550hp Class 33 in 1960–1962

The last locomotive built was the 2,750hp 'demonstrator' D0260 Lion which was completed during 1962. This locomotive was built as an industrial partnership between BRCW, AEI & Sulzer, in an attempt to win a large order (500+) of diesel locomotives, Sulzer were looking for further orders for its 12LDA28 engine, which was already in service in locomotives in the United Kingdom, France and Roumania. This second round of 'improved' Type 4 locomotives were expected to not exceed an axle loading of 19 tons, with 2,500hp called for, plus an additional 250hp for supplying electric train heating. D0260 was in competition with two other 'demonstrators', D0280 Falcon, built by Brush, Loughborough and powered by two Maybach high speed engines, and DP2 built by English Electric and powered by a 2,700hp medium speed engine.

For these prototype locomotives one of the major concerns was the axle-loading. The early diesel electric Type 4's had required four axle bogies to manage their 130+tons, in contrast to similar twin engine equipped diesel hydraulic locomotives weighing in at 108 tons, and 99 ton Deltic locomotives which utilised two light weight high speed engines but with electric transmission. The conundrum was further complicated by the British Transport Commission showing a preference towards those locomotives equipped with medium speed engines, with the electric transmission preferred.

In all three cases the locomotives rode on two three-axle bogies which immediately dictated the use of locomotive bodies where the bodysides formed the main load-carrying members, thus alleviating the need for heavy frames found in some of the earlier Modernisation Plan designs.

![]()

D0260 - Service History

1962

On February 2nd 1962 D0260 was noted at High Wycombe on a test train, headcode 1Z01. For the test runs two tutor drivers from Wolverhampton Stafford Road shed (the nearest BR shed to BRCW Smethwick) operated the locomotive initially between Birmingham & Shrewsbury.

During the first week of April 1962 as newly built BRCW Type 2's D5379/80/81 were being placed into traffic after release from Smethwick, D0260 Lion was noted in the Works yard complete and painted in its white livery.

After shakedown tests at the BRCW factory and running-in turns between Birmingham, Shrewsbury & Banbury with loads up to twenty coaches, D0260 visited Marylebone station on May 6th 1962 for inspection by the British Transport Commission & Crown Agents. Following this it commenced service on Western Region duties on May 14th 1962 between Paddington & Wolverhampton working two daily round trips:

7.25am Wolverhampton - Paddington

1M13 12.10 Paddington - Birkenhead to Wolverhampton

3.35pm Wolverhampton - Paddington

7.10pm Paddington - Shrewsbury to Wolverhampton

Trouble came on May 17th 1962 when the main generator flashed over whilst the locomotive was passing through Leamington. Repairs were made at Smethwick with main line duties recommencing on May 25th 1962. D0260 was noted at Marylebone on May 28th. The following month passenger and van trains were worked between Paddington & Swindon, this included the afternoon 3C07 Paddington - Bristol parcels train as far as Swindon. When working this parcels train the fine lines and white livery of D0260 presented quite a contrast to its lengthy and very mixed selection of parcels wagons. Only a small group of drivers from Swindon and Old Oak Common were trained in the operation of D0260.

Between July 24th 1962 and August 16th 1962 D0260 took part in dynamometer testing over different routes. Initial testing involved a variety of loads being hauled between Swindon & Bristol. On August 8th (or 14th?) 1962 the route changed with 569 tons being taken from Swindon to Plymouth which included standing starts on Rattery, Hemerdon & Dainton banks. The next day the load was increased to 629 tons operating between Swindon, Bristol and Birmingham which included operation over the Lickey incline. Standing starts were made on Lickey, with a load of 16 coaches (519 tons) 20mph was attained at the summit, and with 20 coaches (639 tons) 17 mph was reached at the summit.

During September 1962 the locomotive returned to Smethwick to allow repairs to be carried out on faults detected during the recent tests. The opportunity was taken to carry out further work on D0260.

1963

D0260 would not return to service until March 1963 when it was further tested on the Paddington - Birmingham route with loads up to twenty coaches, including trips over the Lickey incline. Between the test runs D0260 made several trips back to Smethwick for repairs and adjustments. These adjustments eventually gave good test results late in August 1963.

In March 1963 D0260 was given clearance for Whitemoor, presuambly to allow testing on the Mansfield - Whitemoor coals trains.

On September 9th 1963 D0260 was transferred to the Eastern Region, running light from Birmingham to Leeds and then on to Finsbury Park. After crew training was completed the locomotive was utilised on the Kings Cross - Leeds/Harrogate 'Yorkshire Pullman' service, and included some freight workings.

On September 15th there were 26 diesels noted at Finsbury Park including D5057, D5066, D5068, D5072, D5094, D5095 and D0260 'Lion'.

Towards the end of October 1963 D0260 was noted on the grounds of Doncaster Works, although the reason for its presence here is uncertain, perhaps having the lighting arrangement changed for its headcode boxes.

Notes from AEI engineer Bill Wilson provide some detail of the 'routine' working of D0260 Lion during November & December 1963 (at this time AEI provided two engineers to support the locomotive, each scheduled to handle one round trip per day):

Wednesday October 30th or Thursday October 31st - D0260 released from Doncaster Works, Bill travelled from Derby to Doncaster on 30th, having been reassigned from covering the Metro Vick Co-Bo's at Barrow to D0260 at Doncaster/Finsbury Park;

Friday November 1st - in service from Finsbury Park;

Saturday November 9th 1963 - maintenance on locomotive;

Monday November 11th 1963 - with locomotive in service;

Tuesday November 12th 1963 AEI engineer travels passenger to Doncaster following failure of locomotive in the early hours of Tuesday 12th on the Sheffield - Kings Cross overnight goods (at Newark?);

Wednesday November 13th 1963 to Friday November 15th 1963 at Doncaster Works for repairs to control cubicle - repairs to the bus-bar/cable connections (DOC 3376).

The locomotive did not re-enter service until Wednesday November 27th 1963, reaching Finsbury Park late in the day.

Saturday December 14th 1963 to Friday December 21st 1963: running and/or stopped at Finsbuary Park for maintenance, including temporary repairs to the header tank. (DOC 3364).

Of the two AEI engineers allocated to the locomotive, one was ill on December 17th/18th/19th, the remaining engineer rode the locomotive day & night, from approx 9am to 6.30am the next day.

Saturday December 21st 1963 to Monday December 23rd 1964: stopped at Finsbury Park for repairs, including temporary repairs to the header tank. (DOC 3363)

December 24th to Dec 27th - Christmas holiday (no AEI engineers available to man the locomotive)

Monday December 30th 1963 to Friday January 3rd 1964: stopped at Finsbury Park for repairs. (DOC 3362)

1964

Whilst working on January 20th 1964 the locomotive suffered a severe flashover near Huntington. The locomotive returned to Smethwick for repairs, at which time the power unit was found to have a cracked sump. Up to this point D0260 had accumulated approxiamately 80,000 miles.

Unfortunately time had run out not only for D0260 but also the company that had built it, the worsening financial condition of BRCW left the company only one option, to close its doors. With the D0260 Lion project now officially over the locomotive was taken to the AEI facility at Attercliffe, here the Sulzer engine and cooling group was removed and returned to Sulzer, whilst all over reuseable equipment was removed and retained by AEI. The bodyshell was taken to T W Ward for final scrapping.

Specifications - Mechanical

Weight: 114 tons (fully supplied), 103 tons (net)

Height: 12ft 9in

Width: 8ft 10in

Length over buffers: 63ft 6in

Wheelbase: 50ft 9in

Bogie pivot centers: 36ft 3in

Bogie wheelbase: 14ft 6in

Wheel diameter: 3ft 9in

Axle load: 19 tons

Axlebox: SKF roller-bearing

Route availability: 6

Minimum curve: 4 chains

Maximum speed: 100mph

Drawings published in 1961 show the outline of a six axle locomotive bearing great similarity to D0260 Lion, in particular the roof profile. These would most likely have been part of a response to an Eastern Region requirement for a second generation Type 4 locomotive.

The underframe was an all welded structure. Solebars of 'Z' section ran the length of the locomotive and formed the bottom part of the bodyside structure. Cross members linked the two solebars at criticals parts, such as the location of the engine/generator set and the boiler equipment. Inner sidebars of rolled-steel channel section ran between the cross members. Longitudinal pressed steel channel was used to support the deck. Beneath the power unit the deck followed the contours of the sump and allowed for capture of fluids.

The body used steel for all stressed parts to assist in weight savings, under static conditions the body was tested to a maximum end-load of 200 tons. The bodysides formed the main load-carrying members so that the weight of the equipment was supported with minimum deflection. The sides were in the form of a "Virendeel" truss (unlike most trusses which have triangular sections, the Virendeel truss uses rectangular sections to carry the load and is most commonly found in buildings) being a welded assembly of mild steel plate and pressings with a final skin of 14 gauge steel plate. The main bulkheads between the cabs and the engine room were three inches thick and insulated with fibreglass wool.

Fibreglass was used in non-loading bearing areas such as doors and roof panels. The roof panel which allowed access to the engine compartment was pneumatically operated. Unlike earlier designs, air for the radiators, which were roof mounted and air for combustion was drawn through panels in the roof, leaving the body sides free from any openings. This simplified the design of the bodysides and reduced the ingress of dirt and other particulate matter into the oil wetted filters.

The auxiliary equipment, wherever possible, was in the form of self-contained sub-assemblies, to facilitate removal for overhaul.

The bogie frame was of mild steel fabricated construction, stress relieved after completion of welding. The bogies incorporated the Alsthom system of twin rubber-cone, body support pivots and radius-arm guided axleboxes, the first use of such technology in a diesel electric locomotive on British Railways. The increased use of rubber components had the aim of securing good riding qualities at all speeds, and reducing wearing surfaces to a minimum.

Similarities with regard to the external appearance of D0260 Lion and the Beyer Peacock built Class 35 Hymeks was due to the external styling being managed by Wilkes & Ashmore, they were also involved with the Class 47 syling.

Specifications - Power unit

Engine: Sulzer 12LDA28C

Cylinder bore & stroke: 280mm x 360mm (11.02in x 14.17in)

Lube oil capacity: 125 gallons

Engine weight: Dry - 20.7 tons; Wet - 22.2 tons

Horsepower: 2,750hp, at rail: 2,080hp

Tractive effort: 30,000lb at 25.5mph; 55,000lb at 100mph

The 12LDA28C engine was the final development of 12 cylinder LDA range of engines. The continuous output of 2,750 hp designated it at the time as the most powerful rail-traction diesel engine in Western Europe. The increased output was obtained by improving the intercooling system and raising the nominal crankshaft speed. The full-load crankshaft speed was now 800rpm compared with 750rpm in the 'B' series engine.

Cooling of the incoming charge-air was accomplished using the main engine cooling water, thus eliminating a separate water circuit with its associated pumps, radiators and piping. Although this put more heat into main engine cooling water, the temperature of this water increased by only 5F, despite having circulated through the oil heat-exchanger and the two intercoolers in parallel to the engine water jacket.

After the cancellation of the D0260 Lion project the power unit was returned to Sulzer and sent to Vickers Armstrongs for incorporation into the schedule of the power units destined for the Class 47's.

Specifications - Electrical equipment

Main generator: AEI TG5303

Auxiliary generator: AEI TG105

Electric Train Heating generator: AEI AG106 DC, 800V 384 kW

Traction Motors: AEI TH253 (6) - permanently connected in parallel.

Radiator fan motors: two 26.8hp, series or parallel operation

Traction motor blowers: two 7.8hp, series or parallel operation

Combined Pumpset: 15hp motor (to operate the water circulating pump, fuel transfer pump & auxiliary lubricating oil pump)

Exhausters: two Northey Type 125 RE/FM

Compressor: Westinghouse Type 2EC 38B supplying air at 100lb psi.

The main generator and train heating generator were built on a common frame with their armatures mounted on a common shaft supported by a single bearing. The auxiliary generator was overhung from the main generator, its armature being an extension of the main shaft. The use of silicone insulating materials in the main generator allowed the size and weight of this machine to be kept low in order to achieve the required axle loading. The AEI TG5303 main generator was the first attempt by AEI at a high power machine.

The generator supplying the electric train heating load also supplied power to the radiator fan, traction motor blower motors and the traction generator field excitation. The driver's master controller included a 'Top' position, which when selected diverted the power from the electric train heating equipment to the traction motors or, if the electric train heating was not in use the engine speed was increased raised to give a corresponding increase in power output for traction purposes.

The AEI Type 253 traction motors were being used for the first time on British Railways. In the application for D0260 the motors had two stages of field weakening in conjunction with a 17/70 gear ratio, which gave a maximum service speed of 100mph. The motors were nose-suspended, axle-hung, force ventilated and equipped with a lap-wound armature. Its choice was also important because its small volume and low weight in relation to its high torque and power output. These motors would be used in the Class 25/1, 25/2 & 25/3 build and in a number of overseas narrow gauge locomotives, where their small size was of great benefit.

Specifications - Miscellaneous

Brakes, Westinghouse: Locomotive - Air; Train - Vacuum

Brake Force: 58 tons

Sanding: Pneumatic

Steam Heating: Spanner Mk IIIB oil fired, maximum supply 2,500lb/hour at 100lb per sq in.

Boiler water capacity: 1,260 gallons

Fuel tank capacity: 850 gallons

Cooling water capacity: 400 gallons

A selector switch on the driver's desk was used to indicate which method of train heating was to be used, once selected the operation of the heating equipment was automatic.

The arrangement of the driver's controls followed standard practice adopted by British Railways for main line diesel-electric locomotives.

A contemporary styling had been adopted for the cab interior, which was finished in grey and blue with polished timber fascias.

Equipment Location

No.1 end:

Two roof mounted radiator panels with motor-driven fans and ducting.

Train heating boiler, air reservoirs, radiator drain tank, auxiliary machine group consisting of the air compressor, a traction motor blower, and a combined pump set

Brake system components and the engine instruments

Center:

Engine-generator set

Four fuel tanks, two at each end of the engine/generator set

Exhaust silencer located above the generator

Boiler water supply & batteries slung under the frame between the bogies

No.2 end:

Control cubical

Auxiliary machines consisting of the second traction motor blower and two exhauster sets

Brake equipment cubicle

Roof mounted load regulator and resister units.

![]()

Hindsight

The late 1950's & early 1960's was a period of great opportunity for railway manufacturers involved in the supply of locomotives to British Railways. The ordered strategy of the 1955 Modernisation Plan had fallen by the wayside. Now the urgent plan was to dieselise the network on an area by area basis as soon as possible in the hope of stemming the mounting loss on British Railways. And with large amounts of money ready to make this happen, what could go wrong? For BRCW & D0260 it was a series of events, some seemingly unconnected, coming from a variety of sources that certainly sealed the fate of D0260 and most likely that of its builder, BRCW.

Two events which might be considered to have started the chain of events was firstly the change in direction announced on May 23rd 1957 by the BTC to permit large orders of new diesel locomotives without any evaluation period. And secondly requirements coming out of the Eastern Region, as early as 1958, looking for a 2,750hp six axle Type 4 locomotive that was able to negotiate the humps in marshalling yards. This general specification was confirmed by the BTC's Technical Committee on January 15th 1960, with the BTC providing its full approval on February 11th 1960 with the invitation for the submission of competitive tenders. Brush had anticipated these future orders, having already commenced work on what would become D0280 Falcon, but to meet the estimated horsepower requirement they had chosen two quick running engines to power the locomotive, which immediately made D0280 a non-starter for the tender after the BTC confirmed they were looking for one medium speed engine to power the locomotive.

The new Type 4 specification was circulated to the BR Regions early in 1960 with the Eastern Region hoping that Brush would be included in those companies invited to tender, especially in light of the positive experiences gained from their growing fleet of Brush Type 2s. The Eastern Region were also prepared to wait for the delivery of these new Type 4's rather than take the remainder of their allocation of the newly built English Electric & BR/Sulzer Type 4s. In addition to its success with the Brush Type 2 build, Brush had also obtained the contract for the electrical equipment for the BR Derby/Sulzer Type 4s D138 - D193, reportedly due to supply issues at Crompton Parkinson, but also due to a competitive tender which Brush won.

The deadline for tenders was July 12th 1960, with Brush, English Electric, North British Locomotive Co Ltd and a consortium of BRCW/AEI/Sulzer submitting bids. The proposals ranged from GBP 95,250 up to GBP 111,000, with not every bid meeting all the required specifications. The tender submitted by the BRCW/AEI/Sulzer consortium at GBP 103,202 was accepted by the BTC Technical Committe on September 23rd 1960. BRCW's success was somewhat hollow because despite a percieved urgency to dieselise at a rapid pace there was as yet no firm order of Type 4s for BRCW to begin constructing. The BTC would require discussions with the Eastern Region since they would be the owner of the completed order. BRCW would not want to start construction without this firm order although they did state that D0260 Lion was under construction.

To expand on the above paragraph the Technical Committee minute 866(b) reads: "The Committee agreed that on technical grounds, and having due regard to tender price, the most suitable design at present available for adoption as the standard Type 4 diesel electric locomotive was that recommended by the CME and CEE namely that offered by AEI and BRCW jointly having a Sulzer engine of 2,750hp. They agreed however that before orders are placed for the 98 locomotives required by the Eastern Region for their Kings Cross and Sheffield schemes authorised by Works & Equipment Committee minute 1611/7 - 3/12/59, discussions should take place with the General Manager of the Eastern Region and the Technical Advisor was asked to arrange accordingly".

In November 1960 executives from Brush & Sulzer met to see what pressure could be brought upon the BTC to enable Brush to build Type 4 locomotives with Sulzer engines. It was known that the Eastern Region were keen on Brush products, since many of the Brush Type 2s were now in use with the Region.

The journey turned a little bumpier when the issue of the last batch of BR/Sulzer Type 4's (D194 - D199, D1500 - D1513) became the subject of the BTC Works & Equipment Committee which met on February 7th 1961. With the BR/Sulzer Type 4 design now superceded the decision was made to cancel the final order of twenty locomotives and ask Brush to use the electrical equipment in twenty locomotives of the new design. This decision created new discussions concerning the previously accepted BRCW/AEI/Sulzer bid with regard to the changing circumstances. Bids for these twenty locomotives went in favour of Brush, their bid being GBP 113,250 versus GBP 120,000 from BRCW. On March 2nd 1961 the BTC Supply Committee ratified the purchase.

By now there were other clouds on the horizon for BRCW, with the company's financial standing being of concern to the BTC in regard to the upcoming orders of Type 4 locomotives. BRCW encountered difficulties in the completion of an order of bogie bolster wagons for BR and had pulled out of a contract to build 450 coaches for London Transport Underground. On April 10th 1961 the chairman of BRCW, Mr F Newman met with the BTC Chief Contracts Officer, Mr S Robbins who advised the company that future tenders from BRCW may require a Performance Bond to ensure completion of the orders.

During December 1961 consideration was given to the purchase of a further sixty three Type 4 locomotives. There was an urgency to the order - British Railways Crewe Works were to build some of these Type 4's, it was hoped a smooth transition could take place between the building of the final Western Region diesel hydraulic Type 4s and the commencement of the new Type 4 order. It was also felt that giving the order to Brush would provide more chance of standardisation. The BTC quickly confirmed the order, 30 locomotives to be built by Brush and 33 locomotives to be built at Crewe, with all the electrical equipment to be provided by Brush. AEI had bid on the electrical equipment for the Crewe built locomotives, but the lower bid from Brush was accepted. Slowly but surely BRCW was losing its chances for obtaining part of these future large orders.

By April/May 1962 D0260 Lion was being tested on British Railways.

Late in June 1962 the tendering process commenced for a further 279 Type 4's, with the Brush design now adopted as standard. 150 of these locomotives would be built by private contractors. Submissions came from BR Workshops, Brush, AEI & Clayton Engineering in response to the Brush design whilst tenders from AEI, BRCW & English Electric were for construction of their own designs. For building fifty locomotives the pricing varied between GBP 100,860 & GBP 121,644 each. BRCW submitted two tenders, one based on D0260 with a cost of GBP 102,054 for 150 locomotives and an alternative using Crompton Parkinson electrical equipment at the slightly higher cost of GBP 103,568 for 150 locomotives. These bids, and a similar AEI one were rejected due to the use of the Alsthom fabricated bogie, the bogie was not acceptable to BR at this time.

The BTC Supply Committee met late in June 1962 to review details prepared by the Supplies & Contracts Department, the proposal was amended before presentation to the BTC on July 12th 1962, the recommendation being that Brush would supply one hundred locomotives and ninety nine sets of power equipment. For BRCW & AEI the battle was over, Brush's success with these early orders would continue as the BTC returned to them for more orders, eventually to the total of 512.

![]()

Life with the Lion

An AEI engineer details his brief time with D0260 Lion.

From February 3rd 1959 until October 25th 1963 I was an indentured apprentice with The British Thomson-Houston Company, Rugby, a company which was later to become a partner of Metropolitan Vickers, Manchester, within Associated Electrical Industries ( AEI ). Part way through my training, my indenture was transferred to AEI.

Having graduated from university, and having also completed my apprenticeship, in late October 1963 I was given a position on the staff of the Railway Traction Department of AEI, Manchester. My very first assignment was to the prototype Type 4 diesel-electric locomotive D 0260, Lion. I was almost twenty-four. At this time the locomotive was based at Finsbury Park Depot and, resplendent in its predominantly white, gold-lined livery, was operating out of King’s Cross. I was told to report – in London - to one Phil Webber, an AEI traction engineer who was riding with the locomotive at that time. Phil, a kindly and helpful man, was older and more experienced than I. He was staying in a hotel in Birkenhead Street, directly opposite King’s Cross Station, and I was advised, or perhaps even required, to stay there too. From memory, I believe we shared a room but, since in any one week one of us was to do the night-shift and the other the day-shift, we crossed paths but briefly, and any snorings would not have been mutually disturbing.

Phil showed me over the locomotive and handed me several drawings and circuit diagrams to study. During my apprenticeship I had had diverse experience of a range of the company’s locomotives then in service with British Railways, including the testing and commissioning of the prototype 25 kV a.c. locomotives and multiple units at Crewe, the Class 25 diesel-electrics at Derby, and the unusual, Metro-Vick/Crossley two-stroke, diesel-electric Co-Bos at Barrow-in-Furness. I was confident of my understanding of the basic workings of such locomotives, and of the logic of their control-circuitry, but was not at all familiar with the detailed layout of the equipment on Lion. My first task, therefore, was to get to know where everything was, and to keep my fingers crossed that nothing would go wrong during my first solo week in traffic with the locomotive.

In principle, Phil’s and my shared designated task was a straightforward one - viz. to ride with the locomotive at all times, and to be ready to sort out any problems it might have. In practice, things were not that straightforward. As a young greenhorn, I was not privy to the politics of the situation but, strictly speaking, as employees of AEI, our responsibility was possibly for the electrical equipment alone. Responsibility for the diesel-engine lay with the engine manufacturer, Sulzer, and I presume responsibility for the locomotive as a whole lay with the main contractor, The Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company (B.R.C.W.) in whose Smethwick works Lion had been built. Sulzer had a resident engineer at Finsbury Park Depot, but there was seemingly no representation from B.R.C.W. This was to cause us problems. I first had a part-week on day-shift, but my first full week of duty was on night-shift.

During this particular period, and when fully fit for duty, Lion was off-depot, manned, and thus effectively ‘in service’ for about twenty-one hours out of each twenty-four, making two round trips from King’s Cross to Sheffield in that time - a total daily mileage of something in excess of 700. These journeys comprised three prestigious Pullman trains, and an overnight goods train to return the locomotive to London. Inevitably there was also a measure of low-activity, ‘hanging around’ between actual departure times, including visits to refuelling points. On night-shift, I would sometimes have to go up to Finsbury Park Depot to board the locomotive there; at other times Phil would stay with the engine and we’d swap places at King’s Cross. The night-duty comprised a Pullman passenger service to Sheffield (with, as I recall, a departure time from King’s Cross at either 7.00 or 7.30 p.m.) and then the overnight haulage of the goods train - comprised mostly of 4-wheeled vans - from Sheffield back to King’s Cross. Departure from Sheffield was around midnight, and, as I recall, we got to King’s Cross around 6.00 a.m. or later. More frequently than one might perhaps today suppose, we were signalled down to a halt en route – a track-side detector having spotted a hot axle-box. The offending wagon would have to be dealt with at the first opportunity, and the journey could then resume.

In the winters of the 1960s, fog and smog were still commonplace, and a strong memory I have is of peering ahead into very murky nothingness as Lion dashed all but blind-folded up the East Coast Main Line as far as Retford, relying heavily on the bell and horn of the A.W.S., and the sometime presence of colour-light signals, to keep us informed and safe. Thrilling it undoubtedly was, but Lion’s driver and secondman were more relaxed about it than was I! At Retford we turned off left for Sheffield and groped our way slowly from semaphore signal to semaphore signal – losing time heavily all the way. Not at all what our Pullman passengers wanted. My tentative recollection is that, at that time, A.W.S. was not available to us on that last part of the journey. On such days of very late running, I kept my head well down upon arrival at Sheffield.

In contrast, in fine, daylight weather, with Lion sprinting freely over the Lincolnshire fens, and whilst standing for a while in the front cab with head held high, I would quite often spot pheasants perched gormlessly on the rails some distance ahead. Despite the noise of our coming, and even despite our sometime best endeavours with the locomotive’s horn, they would usually stay put and, at the day’s end, we would find ourselves cleaning their bloodied flesh and feathers from around the traction motors.

Travelling swiftly south one day in thickish fog somewhere near Grantham, the three of us in the front cab had an alarming experience - Lion hit something solid and metallic on the track. Some sort of rail-jack our driver thought, and we saw shadowy figures scattering in the murk. I think we perhaps also triggered a detonator. It seems that, despite the fog, the local track-gang was out. They and we had a scare. The driver opined that it was the piece-work payment system that had tempted the track-gang into such reckless behaviour.

In mid-November 1963, also heading south, but at night and at the head of the goods-train, my colleague Phil had a different sort of scare – namely the well-known, but thus far only partially documented, so-called ‘explosion’ in the locomotive’s control cubicle which brought Lion and its train to an ignominious halt. Lion was taken off the train and, later in the day, towed to Doncaster Works. That same day I travelled up to Doncaster to join Phil, and to view the damage. It transpired that the spectacular but technically relatively minor fault was the result of a small error which had seemingly been inadvertently built into the locomotive at either the design or construction stage. The currents drawn by traction motors can be very high – many hundreds of amperes - and in order to carry these large currents safely, it is necessary that both the rigid busbars and the flexible cables employed shall be of large cross-sectional area. In the locomotive of the 1960s, where copper busbars and cables met, the substantial, heavy-duty terminal on the end of the cable was bolted to the busbar. This approach involves drilling a large diameter hole through the busbar to accept the bolt. This hole, in turn, reduces the residual area of copper available for carrying current within the busbar. In Lion as built, this residual area was perhaps marginally too small and, over the preceding months, the busbar may perhaps have over-heated from time to time, possibly causing the securing bolts to expand and contract and even to loosen slightly, and thus giving opportunity for the contact surfaces to start to oxidize. As a result, hidden, high-resistance hot-spots could have begun to develop. Beyond a certain point, this process was probably a self-feeding, accelerating one and, in the dark of a November night, part of the busbar eventually ‘blew’ like a giant fuse. As stated above, the locomotive was towed to Doncaster works and, after discussion with, and inspection by, the AEI design engineers, the pertinent part of the cubicle was rebuilt with busbars of increased width and cross-section. Problem solved. All told, the repair took two weeks, at the end of which Lion put in a working turn to take herself, Phil, and me back down to London, to King’s Cross, and to Finsbury Park Depot.

Whether heading north or south, the gradient known as Stoke Bank, just south of Grantham, was always of interest. In 1938, Stoke Bank had been the site of Mallard’s record-breaking triumph – on that occasion the locomotive and its lightish train were travelling southwards, and thus down the bank. A quarter of a century later, and going in the opposite direction, the footplate crew of Lion would usually be keen to see how fast she could haul her heavyish train up the demanding gradient. I recall I once enthused that we were holding sixty m.p.h. “That’s nothing”, said the young secondman, “with the steamers we used to come up here with ninety on the clock”. Ninety miles an hour up this bank? With a steam locomotive? Surely not I thought! The leathery-skinned, sceptical, wise old driver raised an eyebrow and looked quizzically at his young colleague. “Aye”, added the latter, grinning, “90 on the pressure-gauge”. It was a good, appreciated joke, for, on a large steam locomotive of the time, the boiler pressure-gauge should normally be reading something around 200 p.s.i. ( pounds force per square inch ). If, when ascending a gradient such as Stoke Bank with a heavy train, the boiler pressure really had been dragged down to only 90, then any steam locomotive so placed would be very much struggling, ‘gasping for breath’, and possibly about to expire to a halt; the driver would be cursing the fireman, and the fireman would be red-faced and very busy indeed ! Yes – a good joke!

For its part, Lion was a good locomotive, and quite probably had the potential to be an excellent one, but, like most prototypes, she experienced teething troubles. Some of these had arisen in the year before I was assigned to her, and had presumably been overcome, but some niggles remained, and one was of daily concern to us. It involved the electrical interface between the mechanical governor of the diesel engine and the electrical load-regulator controlling the output of the traction generator. Fifty years on, the details of the circuitry escape me, but the essence of the problem was that, at times, a pair of electrical contacts on top of the governor moved apart so slowly that they drew an arc, causing the contacts to burn and to develop pitting, together with small, elevated, globular beads of copper. If left untreated, eventually the contacts would fail, and the control system and the locomotive with them. Capacitors or other remedial devices were recommended by the design office, and we fitted them to try to overcome the problem, but without success. A daily clean-up of the contact surfaces with a file was all that we at ‘the coal-face’ could do to alleviate the difficulties but, even so, from time to time we still got caught out. At a later date, a colleague other than Phil told of once coming out of Sheffield with Lion and “having to heave as hard as he could on the engine fuel-injection rack” in order for locomotive and train to be able to depart the station. Similarly, part way through a journey south, I myself once had to bring the locomotive and its Pullman train home to London by removing the front panel of the control cubicle and pushing the various relays by hand. Luckily, the engine was the appropriate way round so that the control cubicle backed on to the driving cab and the driver could call-out his power requirements to me. I don’t know which of us was the more relieved to make it safely back to King’s Cross and, moreover, on time. Had Lion been adopted as the basis of a fleet of such locomotives, then, in my opinion, that interface between diesel engine governor and the electrical systems is one feature of the design which would certainly have had to have been looked at and changed.

Curiously, a niggle in a less sophisticated part of the locomotive proved to be even more of a problem. A header-tank for the engine cooling-water had split along a fold or seam and was leaking. This probably should have been B.R.C.W’s problem rather than ours, but, as stated earlier, there was no immediate B.R.C.W. presence. The Sulzer representative at Finsbury Park claimed it wasn’t his problem. My recall is that this header tank was a rather flimsy, rectangular affair, mounted up near the roof. I think it was fabricated, and that a welded seam had split – probably due to vibration. As a result, when the diesel engine was running, and to a lesser extent even when it wasn’t, there was a steady discharge of coolant from the split. Things came to a head in the final week of service running before Christmas. The leak had progressively worsened and, ideally, the locomotive should have been taken out of service, the cooling system drained, and the header tank repaired. But that could not be. I have no idea whether British Railways still had any genuine interest in the locomotive at that stage, but I was told that the Russians were showing an interest and my instructions from my boss were to “Keep Lion in traffic at all costs”. (Some years later, the Russians did buy the even more powerful Type 5 Brush prototype, Kestrel ). From my daily log of those times, which I still possess, I see that on Monday December 16th 1963 I went out to a local hardware shop and paid 11 shillings and 7 pence (58p in today’s money) for a tube of plastic metal, 8 feet of rubber tubing, a clip, and a plastic funnel. A week later, I bought some more. With these we attempted to catch and contain the leaking water. Thus it was that a £100,000 locomotive was kept in traffic. At no time, of course, was the locomotive, its crew, or any person or passenger put at risk. Unfortunately, my colleague Phil Webber was then taken ill, could not work, and I was told there was no-one available to replace him. Thus, in the final week of Lion’s duties in the run-up to Christmas 1963, I had to cover both the day and the night-shifts for five consecutive days and nights, sleeping on the floor of the unheated rear cab as best I could - not ideal in December! The rear cab was unheated because, not wholly unreasonably, the designers had ensured that only one cab could be heated (electrically) at any one time – and of course the driving crew up front rightly claimed precedence! We ( Lion and I ) both survived the week but, by the end of it, one of us was a zombie. I hadn’t been able to catch and return all the water, and no doubt some of it found its way into the under floor cable-trunkings and perhaps led to further, future troubles.

Writing of that time reminds me to mention that, in addition to carrying a steam-raising boiler (for the steam-heating of older type carriages), Lion was amongst the first locomotives to be fitted with three (rather than just two) electrical generators; this large, additional machine being dedicated principally to providing current for electrical train-heating. When on load, this extra generator consumed a significant proportion of the output of the diesel engine. Back then, and as I imagine is still true today, when departing King’s Cross with a heavy train, a locomotive and its driver had to cope with more than a mile of demanding, rising gradient within Gas Works Tunnel. For this reason, in earlier times trains were quite often given a helping heave out of King’s Cross from an uncoupled ‘station pilot’ locomotive at the rear. Lion was not so assisted. In consequence, in winter, just before departure time, some of the drivers of Lion would switch off the electrical train heating so as to maximize the power available for traction purposes. This was fine provided they remembered to switch the heating back on again! If they failed to do so, a belated reprimand from a teeth-chattering guard or ticket-collector would put them right at the first scheduled stop! But that first stop could be some way into the journey.

Lion rode well, but was relatively firm in the vertical plane. One small modification I recall having to be made was to the lighting of the route-code indicator boxes on the front of each end of the locomotive. Originally these were lit by several filament lamps, but the filaments could not stand up to the knocks they received as the locomotive traversed the rail-joints of the time, and, as a result, the lamps were having to be regularly replaced – an awkward job which meant grovelling around under the driving desk in order to access them. At some time in late 1963, these several filament lamps were successfully replaced by fewer fluorescent tubes.

An unusual feature of Lion was that the figures and lettering of at least some of the instruments in the driver’s instrument panel were marked in luminous paint and, at night, those instruments were illuminated by invisible ultra-violet light (u/v); the lighting level in the cab as a whole being very low. There must have been some reflection or spillage of the u/v for, whilst the dials showed up markedly and spectacularly well, so too did just the teeth and white collar of the driver – thus presenting something of a ghostly apparition when the rest of his features could scarcely be seen. Most of the drivers I met on Lion were very experienced, elderly, ‘top-link’ men, who were approaching retirement. They appreciated being able to come to work in a neat white collar and tie. Only one persuaded me he really had preferred the footplate of a steam locomotive. To a greater or lesser extent, most seemingly shared the opinion expressed by one old boy that “ The only thing wrong with these diesels is that they came forty b***y years too late!”.

In the week after Christmas 1963, over New Year, and into the first week of January, I helped hold Lion’s paw for just one more week, and I see from my records that we spent the whole of that time in Finsbury Park Depot effecting repairs. The following week I was posted to the Netherlands; my time in the Lion’s den was over.

Bill Wilson. July 2014.

![]()

Diesel Locomotive Works Numbers for BRCW: 1954 - 1962

DEL 1 - DEL 14 Commonwealth Railways NSU Class in 1954 (14)

DEL 15 - DEL 19 Sierra Leone Development Corporation in 1954 (5)

DEL 20 - DEL 31 Córas Iompair Éireann 101 class in 1956–1957 (12)

DEL 32 - DEL 44 Ghana Railway And Harbours Administration (13)

DEL 45 - DEL 91 British Rail Class 26 in 1958–1959 (47)

DEL 92 - DEL 189 British Rail Class 33 in 1960–1962 (98)

DEL 190 - DEL 258 British Rail Class 27 in 1961–1962 (69)

DEL 259 Sierra Leone Development Corporation in 1962 (1)

DEL 2601 Demonstrator for British Rail D0260 Lion in 1962 (1)

![]()

Looking back at BRCW: 1854 - 1963

The Birmingham Railway Carriage & Wagon Works produced a huge amount of rolling stock, some of which is briefly detailed below.

1910

UK - Pullman

Supplied to Metropolitan Railway as buffet cars, named Galatea & Mayflower; survived at least until WWII.

1910

UK - C & G Ayres, Reading

Six plank, two axle coal (?) wagon.

1910

Argentina - FC Buenos Aires al Pacifico (BAP)

Bogie type boxcar, mostly all steel.

Bogie type hopper wagon.

1912

Argentina - FC Buenos Aires al Pacifico (BAP)

Water tank wagon 50,000 litres; indent 1698.

1916

UK - War Department

Two axle five plan wagon (meter gauge).

1917

UK - War Department

Two axle 10ton covered van.

1918

UK - War Department

Two axle covered van with raised brake cabin.

1920

UK - Cleveland Potash Company (Oldbury)

Two axle potash hopper wagon.

1921

Palestine Railways

First Class passenger coach, ten PR Nos.120-129.

1924

UK - Pullman

Rebuild of 1920 Clayton built six-wheel coach to kitchen & parlour car 'Arcadia'.

1925

UK - Pullman

Sold in year of construction to Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL), parlour car name Minerva.

1925

France - CIWL

Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL), parlour car name Minerva (2nd car to carry this name), rebuilt in 1930 for use by UK Southern Railway and renamed Lady Dalziel.

1925

Italy - CIWL

Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL), named Rainbow, in 1927 sold to Egypt, in use until circa 1955.

1926

France - CIWL

Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits (CIWL) / sleeping car.

1926

UK - LMSR

LMSR mail / parcels coach, gangwayed.

1927

Frodingham Iron & Steel, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper No.601 (1)

1928

UK - Pullman

Rebuild of 1925 coach 'Octavia' by BRCW to kitchen & parlour car 'Diamond'.

1928

Egyptian State Railways

Eight Sleeping cars (all steel) WL3570 - WL3577 for Alexandria - Luxor line

Three Pullman parlour cars.

Three Pullman kitchen cars.

1928

Frodingham Iron & Steel, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper 652 - 701 (50)

Appleby Iron, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper 1100 - 1149 (50)

1929

Egypt - Egypt Railways

Two-car articulated three-class steam railcar, total 13 coaches?

1930

Frodingham Iron & Steel, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper 602 - 651 (50)

Appleby Iron, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper 1150 - 1199 (50)

London Midland & Scottish Railway (LMSR)

20 ton coke hopper M299900 - M299999 (100) (LMSR Lot No.552, Diagram No.1729)

UK Southern Railway

Two axle special cattle wagon.

1930

Frodingham Iron & Steel, Scunthorpe

20 ton coke hopper 602 - 651 (50)

Metropolitan Railway: 1930, 1932/33

1930 MW Stock (later classified T stock)

Motor Coach: 212 - 241 (LT2712 - 2741) (30)

Trailer 3rd Class: 521 - 525 (LT9776 - 9780) (5)

Trailer 1st Class: 511 - 520 (LT9722 - 9731) (10)

Driving Trailer: 526 - 535 (LT6712 - 6721) (10)

Equipped with Metro-Vick 275hp motors, buckeye couplings, Westinghouse brakes, electro-pneumatic control gear and SKF & Timken roller bearings for the axleboxes & traction motors. These vehicles formed five new 7-coach trains, known as MW stock. The remaining new vehicles replaced older stock from other sets.

When introduced brand new motor coaches 240 & 241 worked a special train of railway officers and technical press on March 26th 1930 from Baker Street to Wembley Park (and return) to connect with a demonstration run of a BRCW built articulated steam railcar between Wembley Park & Aylesbury and return. The steam railcar was for operation on the Egyptian State Railways. Included in the dignataries were Nigel Gresley & C B Collett, amongst others.

1932/33 MW Stock (later classified T stock)

Motor Coach: 242 - 259 (LT2742 - 2759) (18)

Trailer 3rd Class: 550 - 568 (LT9781 - 9799) (19)

Trailer 1st Class: 569 - 582 (LT9732 - 9745) (14)

Driving Trailer 3rd Class: 536 - 549 (LT6722 - 6735) (14)

Equipped with four GEC 210hp motors, buckeye couplings, Westinghouse brakes, electro-pneumatic control gear and Timken roller bearings for the axleboxes & traction motors. These vehicles formed seven new 8-coach trains, also known as MW stock. The five third class trailers were added to the 1930 MW sets whilst the remainder of the new vehicles replaced older stock.

The MW (later T) stock operated over the electrified lines from Moorgate, Aldgate & Baker Street to Rickmansworth, Watford, Amersham & Chesham. Occasional trips were made to Uxbridge, whilst they operated the service on the Stanmore branch from its opening in 1932 until Bakerloo line trains took over in late 1939.

In general the T stock remained in service until the arrival of the new A60 stock in the late summer of 1961. The final T stock working took place on October 5th 1962.

1931

UK - LMSR

LMSR corridor first class passenger coach. Order 7798.

1933

UK - SECR

Rebuilt 1933 from SECR kitchen car (built 1914) to composite car, in service until 1961 then as camping coach until about 1968.

1934

Sao Paulo Railway, Brazil

Two four-car non-articulated 60mph diesel electric deluxe trains ordered from Armstrong Whitworth with the mechanical trailer portions built by BRCW. They were named Estrella & Planeta for first class service over the 49 miles between Sao Paulo and the port of Santos. The route traversed the cable operated Sierra incline which limited the train length to under 200 feet and weight to 108 tons. The non-powered trailer vehicle included a cab with driving controls with one bogie powered by one English Electric Co. traction motor. All other power equipment was contained in the power car. Although much of the coach construction used steel in many locations, the side panels and roof used aluminium in order to save weight.

1934

UK - LMSR

LMSR vestibule third class passenger coach.

1935

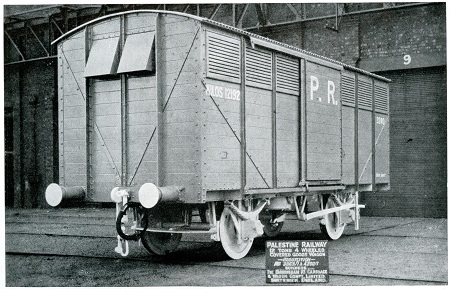

Palestine Railways

Covered 12 ton short-wheelbase goods wagons (number unknown)

1935

Entre Rios Railway

Eleven diesel-mechanical railcars for the standard gauge Entre Rios Railway. Equipped with Gardner engines, Vulcan-Sinclair hydraulic couplings, Wilson epicyclic gearboxes and Lockheed brakes.

1935

Nigerian Railways

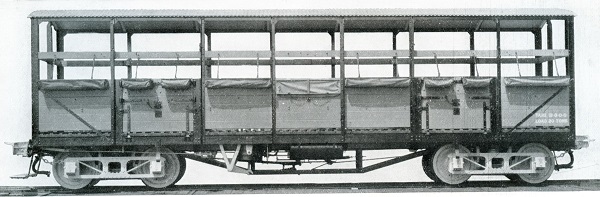

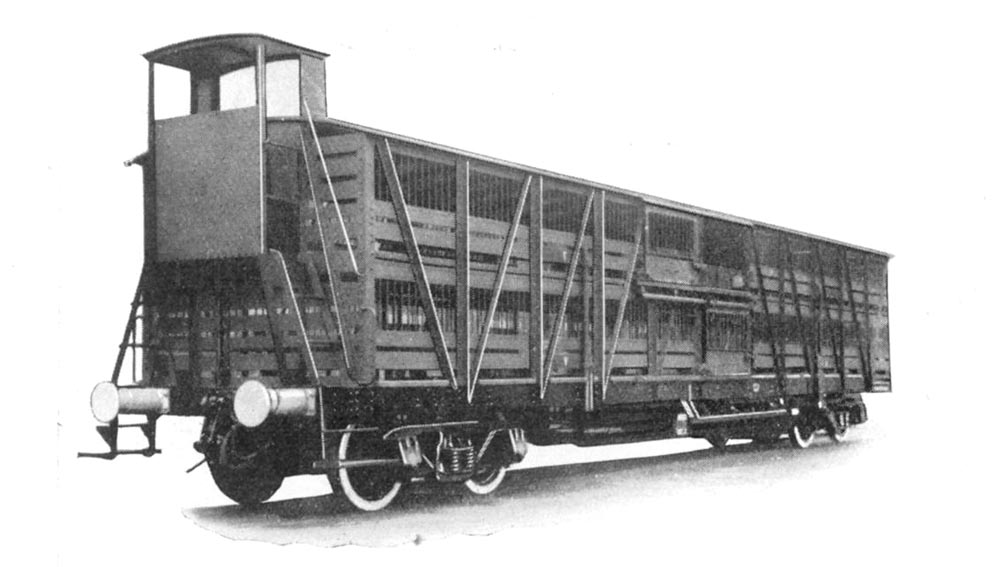

Fifty bogie covered cattle wagons for the Nigerian Railways for use with cattle movements between Kano & Lagos (704 miles). Roofs protect the cattle from the sun whilst the upper third of the sides and ends are open to the weather. Canvas water troughs are carried on each side, chains allow them to be opened up and filled with water when the train is stopped. Length over headstocks 35ft 0in, Height 12ft 0in, Width over stanchions 8ft 1in. (see image below)

1936

London Passenger Transport Board

Fifty eight all-steel two car non-articulated units comprising one driving-motor coach and one control trailer coach. Equipped with automatic couplings, air operated doors, low voltage parallel lighting from a 50-volt supply and electro-pneumatic braking. The trains will replace existing stock on Hammersmith & City Line and the extension to Barking. A further 58 similar two car sets would be built by Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co Ltd.

1936

Canton - Hankow Railway (Chinese Government Purchasing Commission)

Thirty four standard gauge coaches comprised of four 3rd class sleeping cars, five 2nd class day cars, five baggage and guards vans, five baggage and mail vans, five 1st class dining cars, five 1st class sleeping cars and five 2nd class sleeping cars. The coaches will be of all-steel construction, Isothermos axleboxes, Stone's lighting, Westinghouse braking and Vapor heating.

1936

Buenos Ayres Pacific Railway

Two railcars for the Buenos Ayres Pacific Railway, powered by two Leyland Motors Ltd 130bhp diesel engines with hydraulic torque converters.

1936

Peruvian Corporation

Ten 20 ton all steel bogie covered goods wagons and twenty 35 ton bogie flat wagons.

1936

London, Midland & Scottish Railway

200 20-ton bogie hopper wagons with copper bearing steel plates.

1939

1946

UK - Ministry of Supply UNRRA

Two axle covered goods wagon Contract 294/27/R14926.

1950

Iraq Railways: Iraq Petroleum Company 3rd Class and brake coach; indent No.LK58.

Iraq Railways: Iraqi State Railways First & Second Class coach with kitchen; requisition 1212/1.

Iraq Railways: Iraqi State Railways Third Class coach; requisition 1212/1.

Iraq Railways: Iraqi State Railways First & Second Class coach; requisition 1212/1 & 3458/1.

Iraq Railways: Iraqi State Railways Luggage & Brake Van; requisition 1212/1.

1950

Egypt - Egyptian State Railways

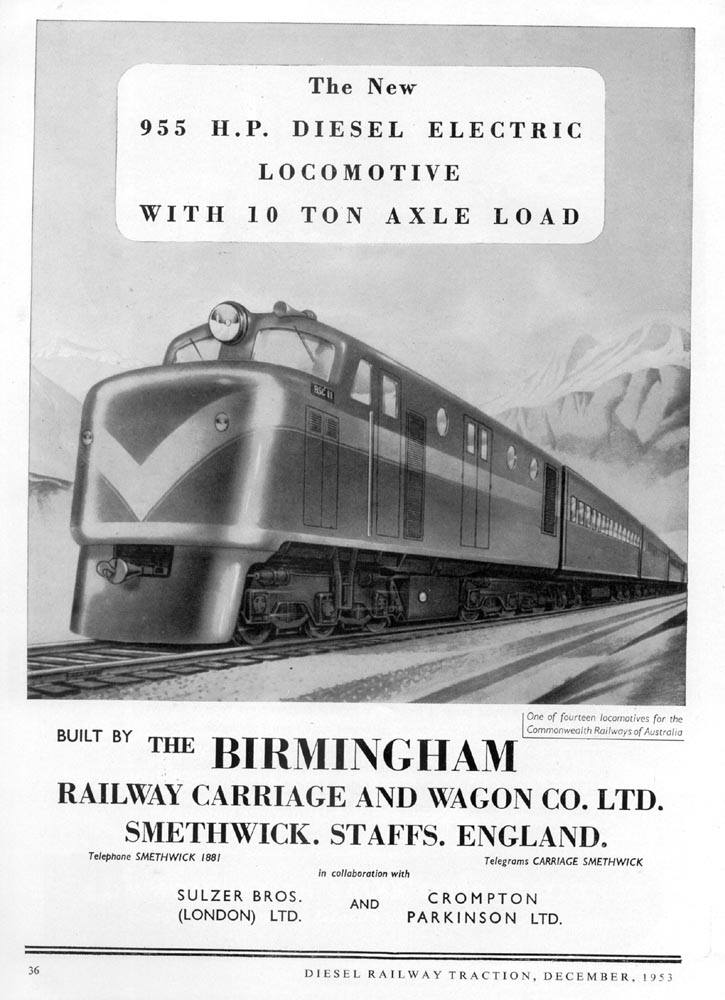

English Electric / BRCW five-car articulated passenger trains; ten trains to work between Cairo & Alexandria.

English Electric / BRCW three-car articulated passenger trains; eleven trains to work between Cairo & Alexandria.

1953

Rolling stock delivered in 1953 included:

Argentina: Covered ventilated bogie wagons

Australia: Victorian Government Railways four wheeled steel open wagons

India: Indian Government Railways (GIPR) Trailer Car 'C'

Forty eight electric multiple unit coaches were built for the Western Railway, India to provide 12 four-car sets for increased services in the Bombay area. The motor coaches were built by Metropolitan-Cammell Carriage & Wagon Co Ltd, with the trailers built by BRCW. BTH supplied the electrical equipment. In order to combat periodic flooding of the lines used by the multiple units the underframe motor equipment was watertight to a height of thirty inches.

1954

The centenary of BRCW occurred during 1954, the output from Smethwick remained impressive with a great variety of rolling stock being produced for delivery to all parts of the world! Deliveries during 1954 included:

Australia: continuing delivery of the narrow gauge NSU class to the Commonwealth Railways.

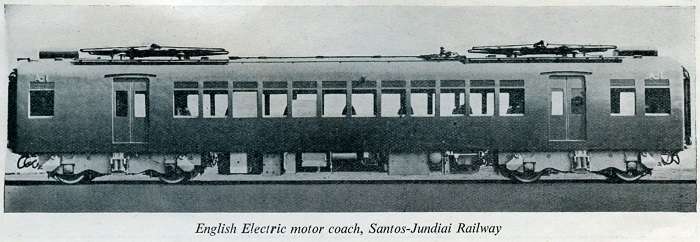

Brazil: Santos A Jundiai Railway - Three-car 3000 volt, 800hp multiple unit (jointly with English Electric) - see image below

Iraq: Iraqi Railways - 1st & 2nd air conditioned Composite carriages; requisition No.1185/1.

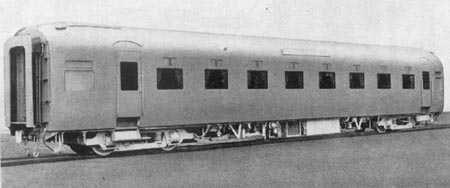

Malaysia: 1st & 2nd Class Day & Night air conditioned carriages, including buffet & sleeping cars (see image below), 3rd Class coaches; Requisition No.368/2

Nyasaland: Nyasaland Railways - 3ft 6in gauge bogie railcar, 200hp, in conjuction with The Drewry Car Co Ltd.

South Africa: South African Railways - 1st Class Motor Coach Type L-48-M

United Kingdom: British Railways - all steel Mk I corridor carriages

The three car electric sets for Santos A Jundiai Railway consisted of two driving trailers and a central motor coach. Tare weight for the train was 111.25 tons with seating for 198 passengers. Although intended for suburban services between Sao Paulo & Pirituba they saw use on express services between Sao Paulo & Campinas covering the 65 miles in 82 minutes with two intermediate stops.

1955

FC Antofagasta & Bolivia: two saloon coaches; specification 675C of Jan 1955.

Nigerian Railway: 1st & 2nd Class sleeping coach; requisition 3592/1.

Nigerian Railway: Special saloon for H.E.The Governor Northern Region; 3'6" gauge; requisition No.3993/1.

1957

Nigerian Railway: brake 3rd Class; requistion Nos.7314/1 & 8735/1 (1956 & 1957).

1958

Ghana: Ghana Railways 13 410bhp diesel electric locomotives built by BRCW with Paxman V engines.

![]()

The formation of British Railways in 1948 provided the opportunity for the renewal of much passenger rolling stock. Large orders were provided to several builders, with BRCW taking a good share.

BR design

24576 - 24675 30057/53 Corridor Second

3003 - 3019 30008/54 Open First Mk I??

4413 - 4472 30226/56-7 Open Second Mk I

4473 - 4487 30227/57 Open Second Mk I

3085 - 3094 30472/59 Open First Mk I

3095 - 3100 30576/59 Open First Mk I

4258 - 4357 30207/56 Open Second Mk 1

4810 - 4829 30473/59 Open Second Mk I

1925 - 1943 30513/59-60 Unclassified Restaurant

1701 - 1738 30512/60-1 Buffet/Restaurant

1618 - 1621 C30511/61 Buffet/Restaurant, 1971 conversion of original 1961 build

1739 - 1754 30527/61 Buffet/Restaurant

24796 30137/54 Corridor Second

80725 - 80802 30140/55-6 Brake Gangwayed

LNER design

59601 - 59608 /54

65601 - 65692 /49

LMSR design

29131 - 29154 1681/56

29155 - 29156 1683/56

29271 - 29289 1011/38

29702 - 29712 1012/38

29821 - 29830 1682/56

29831 - 29832 1684/56

As well as bringing diesel electric locomotive orders to BRCW, the 1955 Modernisation Plan also provided BRCW with a large block of diesel multiple unit orders. The units were delivered between 1957 & 1960 with initial allocations being to the Eastern , London Midland & Western Regions.

The list below details the operating numbers, use in a 2/3/4 car set, TOPS classification, type and year built.

50420 - 50423 (3) Class 104/2 Motor Brake Second 1957

50424 - 50427 (3) Class 104/1 Motor Composite 1957

50428 - 50479 (3) Class 104/2 Motor Brake Second 1957

50480 - 50531 (3) Class 104/1 Motor Composite 1957

50532 - 50541 (2) Class 104/2 Motor Brake Second 1958

50542 - 50593 (4) Class 104/1 Motor Composite 1958

50594 - 50598 (2) Class 104/2 Motor Brake Second 1958

51302 - 51316 (3) Class 118/2 Motor Brake Second 1960

51317 - 51331 (3) Class 118/1 Motor Second 1960

51809 - 51828 (3) Class 110/2 Motor Brake Composite 1961

51829 - 51848 (3) Class 110/1 Motor Composite 1961

52066 - 52075 (3) Class 110/2 Motor Brake Composite 1961

52076 - 52085 (3) Class 110/1 Motor Composite 1961

56175 - 56184 (2) Class 140 Driving Trailer Composite 1957

56185 - 56189 (2) Class 140 Driving Trailer Composite 1958

59132 - 59187 (3) Class 169 Trailer Composite 1957

59188 - 59208 (4) Class 160 Trailer Second 1958

59209 - 59229 (4) Class 166 Trailer Brake Second 1958

59230 - 59234 (4) Class 160 Trailer Second 1958

59240 - 59244 (4) Class 166 Trailer Brake Second 1958

59469 - 59483 (3) Class 174 Trailer Composite 1960

59693 - 59712 (3) Class 163 Trailer Second 1961

59808 - 59817 (3) Class 163 Trailer Second 1960

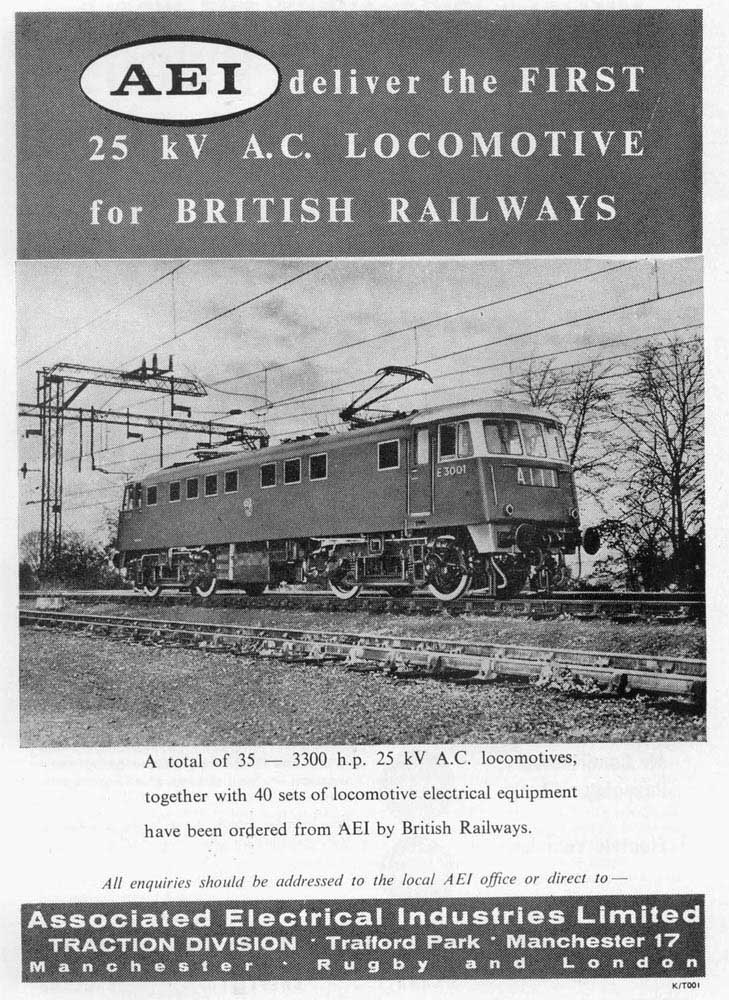

To meet the traction requirements for operating the newly electrified West Coast main line northwards from London Euston, the BTC invited tenders for 100 locomotive. The order for twenty five of these locomotive was awarded to AEI with BRCW as the primary subcontractor, initially classified as AL1, later Class 81 and numbered E3001 - 3023/96/97 (later 81001 - 81022). The mechanical portions of these locomotive were all built at Smethwick and would be the first to be delivered for use on the newly electrified route. E3001 was handed over at Sandbach station on November 27th 1959, the following twenty two were delivered by February 1962, whilst the last two, E3096/97 were put into traffic during June 1962 & February 1964 respectively.

The bogie design was based on Alsthom ideas, using the Alsthom rubber cone pivot for body suspension, Alsthom radius-arm guided axleboxes and an Alsthom secondary suspension system which in part used large rubber conical bearings. A portion of this technology would be used in D0260 Lion. Ironically the Class 81's would become well known for their bad riding qualities.

In service the Class 81's would provide a minimum of two decades of service, apart from three untimely withdrawals due to accident/ fire damage. One of these early casualties, that of E3009, reached the national headlines after its violent collision on a road crossing at Hixon with a heavy goods vehicle carrying a large transformer.

Lots

30293 1957 Class 104 DMU

30294 1957 Class 104 DMU

30295 1957 Class 104 DMU

2880? 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2401 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2552 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2731 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2736 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2930 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2934 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2954 19?? 21T hopper wagon

3030 1957 21T hopper wagon (B423481)

3033 19?? 21T hopper wagon

2907 1958 MINFIT 16ton steel welded body mineral wagon (B550350)

![]()

To complement the entry of Lion into traffic a 16 page publicity brochure was produced, featuring text, drawings and photographs.

A copy of this brochure sold for GBP75.00 on ebay during January 2018.

![]()

Resources:

Sulzer Diesel Locomotives of British Rail; Brian Webb, David & Charles Locomotive Series 1978 ISBN 0715375148

Diesel Railway Traction, July 1962

Promotional Booklet from BRCW describing D0260 Lion

Class 47 Diesels; Taylor, Thorley & Hill, Ian Allan 1979, ISBN 0711009155

AC Electric Locomotives of British Rail; Brian Webb & John Duncan, David & Charles Locomotive Series 1979 ISBN 0715376632

Modern Locomotives Illustrated (magazine); No.174 Main Line Prototypes, The Private Builders; Dec 2008 - Jan 2009 issue

London Transport press releases with regard to MW/T stock

Traction Magazine articles discussing the history of the Class 47's: authors Simon Lilley, John Hiscock & Robert Ward

Bill Wilson: AEI engineer (personal memories).

Page added May 31st 2010.

Last updated September 2nd 2023.